WC

When we started in 1990 our school was attended by children who already had a complete history at other schools. We were searching for an approach that was linked up with our vision. Of course the children were acting from a for them familiar pattern.

So all children asked me ‘if they might go to the WC’. I had groups 4 up and including 8 and had no time to answer those questions. It struck me that if I said ‘that they could determine that themselves’ that children went to the WC very often the first few days. To be honest I thought it was exciting if the children went to the toilet with so much pleasure. However I had always pointed out to myself that I could organize the classroom more interestingly than the toilet. And .. after a few days they came back and only went when they really needed to go. Except for the one who goes more often but that does strike you then!

must agree upon who may go when.

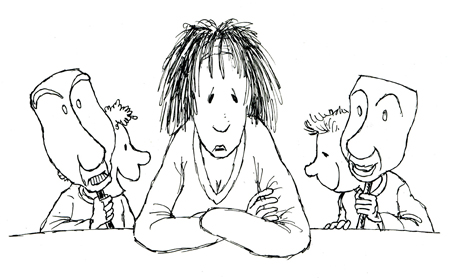

Janneke is a teacher in groups 5/6. She asks me to come in her class. She wants to have a conversation with six boys. She has spoken to them more often about the behaviour that they show towards each other. ‘Tough’ and ‘mad’ that is what the boys call it when they are discussing it. Janneke has the impression that it is harmful to a pleasant, relaxed development. When she asked two days ago what would happen if she ‘played’ someone else the whole day, Kees said: “In fact you are nobody then; not yourself and neither the other person.” The boys had indicated that they in fact did not want it that way. It is also Kees who says when I sit down next to them: “I think that I know what we are going to discuss.” Janneke stretches out two fists in front of her and opens: “You know that we have recently spoken about yourself (she puts up one fist) and the one you are playing when you are acting toughly or madly (and she puts up the other fist.)”

“Yes” Rob says, “then that one (and he points at the fist representing ‘yourself’) is not used.” “And..?” Janneke is inviting. “I am actually curious who the other one is,” Kees says. “But how are you releasing that one?” Joris laughs. The solutions are ‘simply funny’. They think the funniest suggestion is about the zip; you open a zip inside yourself and you open it if you want to show yourself. “In fact we must act normally then,” Jan says. He is also looking at Janneke. I ask him how that could be possible. Kees is beaming: “That is not mad and not tough. So in fact the opposite of ‘mad and tough’, is ‘normal’.”

“Yes,” Jan adds, “so in fact normal is different…” “And that while normal is in fact normal,” Rob finishes. I ask them if they can tell from others if they act normally of in fact toughly or madly. “By the eyes,” Rob says and looks as somebody who is not himself. “I can tell it very well from Joris,” Kees says, “and then he does something, but you can tell by his smile that he in fact does not really want to do it.” Joris distorts his face. “Yes.. that smile…nice, isn’t it.”

Joris shakes his head. And that is what Kees obviously also meant. “How could you help each other in this?” I ask. “By acting normally,” Niels says who had ducked in the sofa so far. Also Gijs opens out: “Yes that you say for example after four times that you must not do it.” “For me you may say it right away,” Niels reacts. “For me too,” Jan shouts. But about that no agreement is reached. “Or wink?” Kees says, while he tries it and experiences that it is not handy.

“No, it is not easy to do that secretly.” Gijs tells that Janneke sometimes mentions his name when he does something that is not good. The others think that is an excellent means, for now everybody knows what it is about. I ask if everybody thinks that we have finished this conversation. “Marleen has heard everything; she has been listening all the time,” Joris says. I ask him if he was going to do arithmetic if we had this conversation with a couple of other children. Joris is laughing scornfully, but he does not risk that they will have to call his name already.

Ara has been a teacher at a school for Experience Oriented Education for three years now. Formerly she planned one or two fixed circles every day. At the moment she determines together with the children at the beginning of the week which circles they want and when. This has increased the involvement very much. In one of the many different kinds of circles, the evaluation circle, Henk (10) tells that he has not worked well in the arithmetic corner for the umpteenth time. He knows that he is to blame himself. He does not take the initiative to look for another seat if he is disturbed. He remarks that he works much better in the language corner. According to Henk that is due to the position of the desks in that corner. He proposes to change the position of the desks in the arithmetic corner. The teacher takes up this proposal and asks Henk if he wants to make a ground-plan of the arithmetic corner with the formation that he likes to see there. Henk agrees on this. Some days later the new formation in the arithmetic corner has been realised according to Henk’s proposal.

Sandra is a new teacher straight from the teachers training college. She still thinks the week openings that she has to lead herself very excitingly. That is why she does this together with a colleague. Together with the whole school they sing the school song. She tells who the persons are celebrating their birthday this week and there is also a song for them. Next to that it also really is her turn. Together with a colleague she does a play as an introduction to the children’s book week. She is the spider in a big web. That her colleague has a giant vacuum cleaner frightens the kids. The higher classes think it is hilarious. Sandra’s week starts with an extremely pleasant feeling.

During the week’s ending on Friday she is relaxed and apparently presents with ease. At the end of the week’s ending Sven (10) comes and calls forward Kamir (4). Kamir wants to show his dwarves’ house which he has made in one of the workshops. Dressed as a dwarf he tells what can be seen inside the dwarves’ house and how dwarves live in it. Together with a lot of dwarf friends he sings a song. He has learnt it during a project about dwarves. The project developed with reference to a dwarf story. Then the children brought everything from home connected with dwarves.

A picture of a monkey which dressed as a goalkeeper is leaning against the goal post. The class is working. I have not discussed his contract letter with Bart. I stick the poster on the door and I put a card on it with: ‘This is Bart.’ I leave the classroom, close the door and I am having a cup of coffee. Coffee, some milk, stirring quietly, drinking slowly and another cup. As if I can see Bart through the door, I am already enjoying his possible reaction. After some ten minutes I cannot hold it any longer. I walk into the class. Everybody is working in an exceptionally ‘quiet’ way.

Without looking I close the door behind me. Bart has a red head that sticks above the arithmetic cupboard. In a powerful way he points at the door behind me. I turn around and read during loud shouting, applause and laughing the texts of more than twenty cards. Many different handwritings have recorded many different comparisons. I recognize Bart’s handwriting. He really thinks I am the monkey.

And I do know that ‘realy’ has double l but I will tell him tomorrow (at the earliest).

Pim had been a teacher at a Jenaplan school for years before he started working at a school for Experience Oriented Education. He was used to a differentiated approach. Most children can cope with a week’s task. Some have individual tasks, adapted to their pace and capacity. For the contract work he can make use of a number of basic principles.

Pim indicates as well as possible before to the children:

1. How much time they get. Planned instructions etc. are in the contract.

2. Which rooms children may use and may not use. Some noisy rooms for example are closed in the morning.

3. What the criteria are. So children must know when they are doing ‘well’.

He distinguishes 4 types of children while working:

1. Children that can work autonomously; they hardly need the teacher.

2. Children that can work autonomously after instruction; they can work independently after they have exchanged strategies and ways of working.

3. Children that have to be taken by the hand (temporarily); they experience insufficient support from ways of working, methods and materials.

4. Children that are working with a plan of action; they are counselled intensively.

His challenge has been every time to get children to a level higher. He keeps asking himself what he can teach the children to be able to do it themselves.

He gives his instructions in a sloping way:

all children that need instruction come together. Pim lets them have a look at the material of the new contract. Children that have questions, ask them to each other or to Pim. Together they exchange strategies. The children that can start working leave. The children that stay behind can go into problems more intensely with Pim. Finally one or two children usually remain which he can counsel separately.

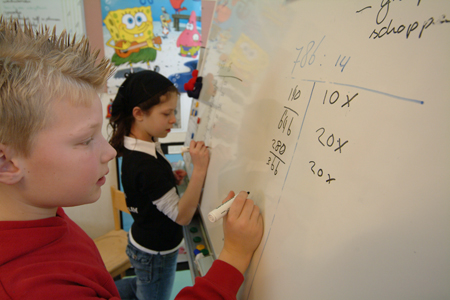

The most difficult thing for Pim is to find out quickly what the real questions of the children are. Nevertheless he has made great progress in this. Some children say they do not understand arithmetic or do not understand assignment 7. Formerly he started to explain immediately. Now he starts the search for the real question. A simple strategy works well in any case. He asks what children do understand, makes them tell and draw themselves. From this it becomes clear what they do not understand yet. He notices more and more often too that children after they have been explaining things to themselves cry ‘Oh yes’ and walk away. He has the children made the habit of asking real questions. For a while he closed the book when children said they did not understand the assignment. Mostly children did not seem to know at all what the assignment was. He was inclined to give an explanation while he in fact did not know what the question was. Now most children are coming to tell already what they do know and what they do not know. Recently Inez came with her arithmetic book. She looked at Pim and said: “I understand everything but I do not want to sit with you for a while.”

Petra (10) is sitting in the arithmetic corner. She puts the headphones on and listens to a cassette on which the tables of up and including 10 are sung. In this way she checks which tables she cannot sing along fluently enough. She makes of the most difficult tables a complete series in her arithmetic exercise book while making use of a table slide. In that way she checks the result of each table so she can be sure that everything is good. Finally she puts on the recorder and tries to sing along with all the tables.

In the evaluation circle she explains what she has been doing. She discovers that she has been doing arithmetic almost the whole morning. She does not mind because she wants to get to know the tables as soon as possible. Moreover she could not stop it. It becomes clear that she has used her time very usefully and that she has learnt much. She thinks that she will have less trouble doing arithmetic in the little shop.

Because I cannot follow them I ask them to draw it. “Tell me what you are drawing and how it works,” is my instruction. Simon begins. He is drawing pistons inside the engine. “Do you know the commercial of those dwarves that are going up and down very quickly and..” I get an idea of how it works. Then he is drawing a connecting shaft. Then he starts again an ‘idle talk’. I am not satisfied with that anymore. I want to know how it exactly works. None of them can tell me that. Karim puts a question mark to it. Then they are starting to draw from the tyres and they start reasoning.

Project work is a series of intrinsically motivated activities of pupils aimed at the exploration of a piece of reality. Project works when children meet with certain questions, problems or themes that strongly appeal to them.

Amaira has worked with project work for years. She thinks a lot has changed since there are computers with an internet connection in the classroom. Some children just want to type a word and then print everything on that ‘project’. It turned out to be a reconnoitring. After arrangements had been made about the use of the internet and the number of prints per person the computer became one of the sources (just like PowerPoint became one of the ways of processing information.) Especially in individual projects it gives children a quick start. But in class projects and school projects there is more attention for doing and discovering things together. Since some time it has been an agreement that children, provided they are well prepared and accompanied by a parent, can set out during school time. Suddenly a lot of initiatives seem attainable and parents are also challenged to visit interesting people and places. Three months after her grandmother died of cancer Cecile (12) comes with the wish to know more about this illness. She starts collecting material. At school she finds nothing at all. In the local library she finds a number of leaflets. The leaflets are from the cancer foundation. She writes to the foundation to ask for material that is suitable for children. In the letter she asks a number of directed questions. She is mainly looking for answers to questions such as: how cancer develops, which kinds of cancer there are, how the chances to survive are for every kind, what the counselling of cancer patients and the people in their environment is like and how big the taboo is to talk about cancer. Furthermore she arranges an interview with somebody she knows and who has had cancer for thirteen years and she wants to have a street interview to find out how big the taboo is. She wants to make a book in which it becomes clear for children of her age that cancer is a life threatening disease about which there is much uncertainty, but with which patients and people in the patient’s direct environment have to cope with difficulties. She wants to present the book to her own group and not to all children of the school.

Working in projects

In former times Nomads travelled around the world in search of areas where surviving was possible. An old story, which has a Hebrew origin, tells that the oldest person of the tribe threw a stick in the morning. People walked into the direction in which the stick pointed. The Hebrew word for throwing is ‘jarra’; the French ‘projeter’ (throwing in front of you) has been derived from this and our word ‘project’ has been derived from that in its turn. In its oldest meaning the direction was determined in ‘the project’ but not the final destination. Literally not, because there was no image of it. That is a beautiful metaphor for our project. By the way that it was the eldest person in the tribe who threw the stick , will not have been a coincidence. He had most experience and knew the circumstances best.

Some time ago Wim had together with his colleagues in the middle and upper forms sufficient parents. Now the interest has become less, all teachers and parents have organised four different workshops in their classrooms. The children choose from the offer and are working in the workshop for four weeks. A retired painter, a volunteer from the first aid association and a judo teacher have taken care of the offer for months. These workshops are still chosen in plenty.

With bright red heads the children are catching their breath in the circle. While other children are reporting about their workshop activities of that afternoon Mart is still panting. When he asks for a turn, he tells excitingly that his condition is improving every time. The exercise lessons to music at the local sports school have taken care of that. When he felt his heartbeat the first time after an exercise, it was 135 beats per minute. Now this is at the same burdening still 120 beats per minute. Proudly he tells that he can follow the movements to rhythm much better. He thinks it is a pity that it will be over very soon, although he is looking forward to the presentation that he will give together with Carl (11) at the sports school. They have already started with the preparations. They have made up movements to the music of Ali B. and are practising together now. Perhaps they are so difficult that the others will not be able to follow them. They want to perform the presentations which they will show to each other in the last lesson at the sports school in a week’s closing.

Sonja has noticed that free choice is not the same as ‘doing what you want to’. For a time she overrated the children or rather: interpreted free choice as ‘doing what you want’. Some children were not activated well because of that. Now she has the offer – the choices – on the blackboard. Children can choose from this and may also always come with a plan of their own. She looks at the plan together with the children so that everyone knows what he has to keep to. Games, technical Lego, chess , draughts etc. are still popular. Nevertheless there are always children who use this time to work on their contract or project.

In the circle the offer of choices for that afternoon is explained. However, two children, Marga and Miranda (both 9) do have an addition to the offer. They are showing a map with examples of filigree which they have made themselves at home. They come up with the suggestion to include this activity in the offer. Then the children make their choices. Five children choose for filigree. They are children of different ages. They find some space in the room for arts and crafts. Marga and Miranda explain to the other children how certain figures must be rolled. In the evaluation circle at the end of the afternoon there is an exhibition table with on it all kinds of rolled filigree figures. The group gets appreciation everywhere and filigree is a fixed part of the free range of choice for a several weeks.