6 |

The concept ‘Experience Oriented Education’ |

From challenge to balance |

| |

| |

| |

| The eleventh order |

|

|

| |

|

| It is twenty-five past one. At half past one we are expected at the library. Normally we need about ten minutes to go from school to the library. So I tell my group 7/8 that it is about high time. I also make clear in my way that I want to leave as soon as possible now. We walk through the corridor, across the playground to the lawn behind the gymnasium. I join the leading group and I walk briskly. |

|

| We cross the lawn to the gates to the through road. I look back and I see Rosa on the back of Sanne. I call them that I want them to cross the road together with us. Rosa jumps off ‘her horse’ and gallops into our direction. For the second time I look back and I am irritated by the fact that Sanne is sauntering carelessly. |

| |

| When we get to the big road Rosa has caught up with the group. Sanne did not change gear. I stand still in front of the group and look at Sanne profoundly from a large distance. Greeting passers by hinder my second compelling request. They do not take away my irritation by any means. The children are silently following Sanne’s provokingly slow march. When Sanne has neared the group at five metres my fierce, agitated voice communicates to her: “You either walk together with us from now on or you are going back to school.” Without a single reaction Sanne turns around and takes two steps into the direction of school. Now I call being really irritated: “You are walking with us, now!” The group is following me silently to the waiting librarian. From the rear I hear sobbing. I do not want to understand it for a moment. I am really angry! |

| |

| In the library I tell about the optional assignments. All children are swarming apart. Sanne remains heavily sobbing in the story corner. I have become quieter and I shove close to her without touching her. “I really do not know why you are crying,” I say. “For my feeling I may be really pissed off with you.” Sanne raises her head, looks at me not understood, breathes deeply and says: “You allowed me to choose. I might go back to school you said and then I was not allowed to.” I was startled by her remark and ask for time to think. When rising I pat with my right hand on her upper leg. “I will be right back.” |

| |

| Walking between hundreds of literary works I remember the words an old, wise woman once said to me. She formulated a self conceived eleventh commandment: “Love yourself in the other person.” The other person enables you to be glad, sad, afraid, fascinated and… pissed off. Sanne made a choice which I had not meant but also a choice I would never have dared to make. Sanne confronted me with my socially desired behaviour. In that respect Sanne is quite a step ahead of me as an eleven-year-old. I would never have turned around. Again I am feeling ‘my’ irritation. |

| |

| I go to her again and I tell her in a simplified way what I have thought. She winks at me. I will do that again tomorrow. |

| |

Children that are doing well

can do well. |

| |

| |

| Experience Oriented Education |

| |

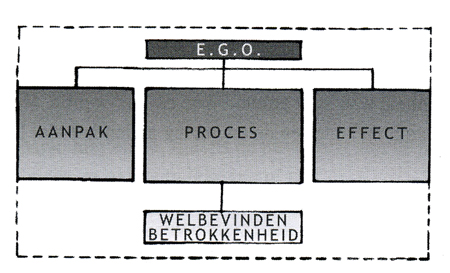

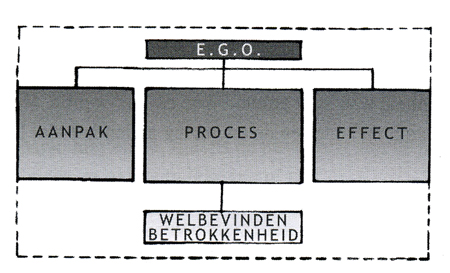

| Professor Ferre Laevers added very important components to the constructivist way of thinking. With the process variables ‘wellbeing’ and ‘involvement’ he gave us criteria to view ‘fundamental learning’. By getting grips on the process side of developments interventions could be made in a more direct way. ‘Putting yourself in the other person’ became the entrance code. |

| |

Experience Oriented Education is interested in the ‘experience stream’ inside the other person.

It is a form of education that challenges people to grow and be fascinated in oneself, in others, their environment and the big total living, at which one tries to feel and tune to what lives inside others and oneself with wellbeing and involvement as criteria. |

| |

Experience Oriented

Experience Oriented means: oriented at what is going on in children’s minds (experience stream). Oriented at the mental and physical instruments and the personal life history with which we enter school. Oriented at what moves and motivates them, oriented at what they ask in view of their development. Oriented not only at the development of cognitive skills but at the total experience of educational learning situations. Oriented also at the accessory positive and negative feelings which all too often have to do with being under pressure of fundamental human needs or not: Children (adults) want to feel physically fine, are in want of affection, are in want of safety, in want of continuity, in want of being someone in the eyes of the others, in want of feeling competent and in want to experience one’s own existence as meaningful.

|

| |

Gendlin* puts it into words as follows:

The experience oriented approach makes it possible in the process of giving meaning to penetrate to the level of the experience of ‘felt meanings’. It is in the experience stream that the perceptions, images, memories, fantasies and thoughts are formed to constitute the ‘affectively experienced situation’ together with the feelings. In one to the utmost performed act of empathy – in which one ’becomes’ the other – one reaches the sharpest possible image of what reality looks like for somebody.

|

| |

| * See also; E. Gendlin, Focussing; feeling and body (1981) |

| |

In that body there is a person that thinks and feels:

The upper seven centimetres of the human being are interesting.

But do you also take into account genes, intestines, desires, prejudices, memories, talents, traumas, gastric juices, mourning processes, examples, white blood cells, failures, anger increasers, joy increasers, capacities, sweat-glands, preferences, susceptibilities, dream causers, nervous twitches, needs and neurotransmitters?

|

| |

| Laevers started his project Experience Oriented Education in 1976. Initially a core group concentrated on searching for a way of socializing which would lead to a better contact with children. The Experience Oriented dialogue en the free initiative developed from this. Children are given space to take initiatives driven by their urge to explore. The belief in the possibilities of children was supplemented by the insight that interventions of adults were indispensable. Boundaries have to take care that every pupil can grow in the best circumstances. |

| |

Freedom is not enough

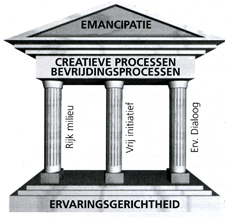

Free initiative in itself is of no use if the offer is poor. A meaningful activity is a result of two factors: options and a rich environment. So the environment is worked on. The teacher becomes a designer and a coach of activities. When in 1979 the temple scheme got its form an important milestone was set in the development of the project. It expressed that real development had priority and that alienation should be prevented. It expressed that this form of education strives for an emancipated human being: a human being that is free in his thinking and moving, a human being that takes responsibility for what he does because he is not called to account. The concept also expressed itself about the attitude of the adult: an Experience Oriented basic attitude became a conscious orientation on what happens in the experience stream of children. A search to find out the uniqueness of the other person.

|

| |

| The temple has three pillars that support the roof. The roof, the striving, is an emancipated human being: free and responsible in thinking and acting. The foundation, the basis, is an Experience Oriented attitude. That is the attitude that is aimed at what happens inside the other person, while you use wellbeing and involvement as standards. |

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| The pillars |

| |

1. Free initiative

Free initiative is a powerful means to enhance involvement. By nature children spontaneously choose activities that are closest to their abilities. In children we see the inner drive to discover the world around them and to explore new possibilities in its purest form. This drive to explore which is naturally present stimulates the independence and increases self-confidence. In this way the child feels competent and wants to develop further.

2. Rich environment

In order to meet the children’s urge to develop a rich environment with enough stimuli is a condition.

A ‘rich environment’ is a classroom or school environment with interesting and challenging materials and activities for children. The organization of the classroom and the school is very determining in this but also the activities which the teacher undertakes. There is attention for diversity. One has to appeal to all areas of development so every child can come into its own. Also the personality of the teacher plays an important role. His creativity and inventiveness belong to the rich environment.

3. Experience Oriented dialogue

The Experience Oriented dialogue is an empathizing way of communicating. That conversation is aimed at the experience stream of the other person; at ‘what happens inside the other.’ Laevers has been inspired by Carl Rogers with regard to this form of communication. Rogers analysed communication into three facets: acceptance, authenticity and empathy. Of course not every conversation has to be held with attention for these aspects. Sometimes it is good or necessary to reject, to ignore or to communicate from your own perspective. But if you want to link up with the needs that children really have attention for acceptance, authenticity and empathy is evident.

|

The Experience Oriented dialogue

During an educational in content meeting a teacher brings in a case referring to a talk about the experience oriented dialogue: “This morning I was sitting near a child who had made a drawing. He asked me to write something to his drawing and dictated: ‘The thieves are going into the machine. They must all be cut into pieces. Then blood is coming out.’ I was so shocked that I did not know what to do. What would you do?”

Karin says: “I would write it down. It is the child’s story.” “I would be shocked too,” Peter-Paul says. “I would let him feel that I was very shocked.” “I would be especially curious why he is drawing this and what is on his mind,” Tina remarks. We do not wonder who is right and what is the best intervention. We are looking at the aspects of the Experienced Oriented dialogue and we state a number of striking elements:

Karin aims especially at acceptance; she takes over as a matter of fact what the child contributes. Peter-Paul intuitively shows his authenticity; the child can tell from his reaction how it ‘enters’ him. Tina feels empathy; she is aiming at what happens inside the child.

The three aspects of Experience Oriented dialogue acceptance, authenticity and empathy seem to get priority in these interventions in a natural way. Each teacher reacts intuitively rather from one aspect than from another.

Then the question does arise: “But what is the best intervention?” Again it does not seem useful to judge from good-bad, let alone that (universally) the best intervention could be pointed out. Everybody has a natural way of reacting, which inclines strongly to one aspect of priority. But because everybody thought his own intuitive aspect important, the insight developed that the limit of that aspect should be defined by the other aspects. Or: it is wonderful that Karin reacts from acceptance, but it is important that she is conscious of her own authenticity and the interest for “what is going on in the child’s head.” It is excellent that the child sees what his story does with Peter-Paul. Peter-Paul should try to keep attention to ‘how this enters the child again.’ And of course Tina may be interested in what happens inside the child’s head. But she should take care that the child can tell from her reaction what his story does to her.

We put Karin to the test. We make up some sentences that she would definitely not write down on the drawing. She notices that there is indeed a limit to what she would write down gratuitously; a limit to her acceptance. She feels that authenticity and empathy are ’at play’ then as a matter of fact.

|

| |

| After the temple scheme a second milestone was set with the concept ‘Involvement’ around 1985. That concept put the project in a rapid. If there is involvement one does feel a teacher knows how to deal with a series of factors well. Moreover, the criterion of involvement gives the teacher immediate feedback: here and now, while putting things into practice one gets to know if one contributes to development or not. |

| |

| At the end of the eighties a new theme shows up in the research and development work: Coming to grips with what education actually realizes in development. It is necessary to picture changes fundamentally; not the superficial learning that you achieve by means of a simple step-by-step method. Within the Experience Oriented Education ‘Learning’ is not seen as a compulsory learning of defined knowledge and skills, which are taught according to fixed methods. ‘Learning’ is seen as a process that takes place inside people driven by their own will. |

| |

| If somebody learns or develops can be told from the level of involvement. Knowledge and skills that a person acquired with a high involvement mean fundamental steps in his development, insights which enhance the grip on himself and the world permanently. That is true for the children which take in hand their development in consultation with the teacher, the present materials and their classmates. But is equally true for the teacher who keeps learning form the unique shapes which the development in children can have. |

| |

| |

| Linkedness |

| |

| Recently Experience Oriented Education has been enriched with a new dimension: “Linkedness”. What Experience Oriented Education strives for is a basic attitude of linkedness with everything that is alive, the experience to be part of history, the universe, the ‘surpassing’. That experience of linkedness ensures that people are going to take care of themselves, the other person, the environment, the world. Working on linkedness in themselves and children means tapping a deeper layer in one’s own experience stream. It means: turning oneself inside, becoming quiet and letting speak the powers that connect us with a greater sensitivity. |

| |

| In Liking School** Stevens describes the problem of the disconnections in education. The disconnection between relationship and achievement, of effort and result, of process and product, of theory and practice, of upbringing and education, of man and work. |

| |

| From another perspective criminologist Anouk Depuydt*** reached the same conclusion. Linkedness was her answer to delinquency. People who are linked to themselves, the other person and the environment will not damage that. |

| |

In 1975 seven South Moluccan youngsters hijack the intercity train from Groningen to Amsterdam near the village of Wijster in the province of Drenthe. They have the train stop in the meadows near level crossing ‘De Punt.’ They have one goal: recognition of the free Moluccan republic in the Netherlands. To show it is serious they issue an ultimatum and point out a passenger who will be executed after that. As a final wish the man dictates a personal letter to them for his wife and children.

Later he describes how, from that moment onwards, the attitude of the hijackers changed: “As if they had got a kind of link with me, which prevented them from doing harm….” This man was ultimately spared. Others were shot without having been allowed to write.

|

| |

| **Stevens, L. Liking School (2002) |

| ***A. Depuydt, Linkedness as answer to de-lin-quen-cy? (2001) |

| |

| |

| Innovation movement |

| |

| The power of Experience Oriented Education exists in the fact that it does not flee the complex reality of education and upbringing but that it tries to put itself constantly in what takes place in children and adults. The Experience Oriented Education has developed in that way into one of the most important innovation movements in Flanders and the Netherlands. In the meantime a broader international emanation of the concept has become a fact. In more than twenty-five countries serious attention for the Experience Oriented has become a way of thinking. |

| |

| For years schools had all been oriented on the product, the result. The methods defined the offer. The traditional innovators have already demanded attention for the uniqueness of children for over a century. That is why the process became more important. However, Laevers added an essential insight to that process: the way in which children develop maximally. If children (and adults) are involved and thus are really totally wrapped up in the activity the development is maximal. And what exceeds a maximal development? Getting involved becomes easier if the wellbeing is good. |

| |

Experience Oriented Education does not turn pupils from lower types of education into grammar school pupils but it turns disinterest into inspiration. |

| |

|

| |

| |

| And what about competence? |

| |

| Wellbeing, involvement and competence are often mentioned in the same breath. The discussion should not be about wellbeing and involvement or competence. Of course children in schools should become more competent. De question remains: How? Wellbeing and involvement are not a goal in itself but a means to come to maximum development. In that respect it is very important that children become competent. But also the term competence is interpreted in a different way all the time. |

| |

| Let us say that it means capability and expertise. And that it is important that school is oriented at children becoming capable in a versatile way. In that respect knowledge and cognition are not discarded notions. Knowledge and cognition are part of becoming more capable. Competence can be seen as a product variable while wellbeing and involvement are process variables. Competence is the result of wellbeing and involvement. In other words: high involvement makes children maximally competent. How far children will get is next to that of course dependent on talent and environment factors. |

| |

Experience Oriented Education does not turn pupils from lower types of education into grammar school pupils but it turns disinterest into inspiration. |

| |

| Wellbeing and involvement are often discussed in a simple way. Students and teachers who study the process variables profoundly and observe the practice from there, speak about them less casually. Coming to grips with these two criteria demands next to knowledge a permanent reflection. This requires being able to take distance and putting oneself in somebody else. But it is also relevant being able to word intuitions and to consider these in the light of jointly formulated conceptual thoughts. Reflections that lead to self-reflections make things can be different tomorrow. |

| |

| |

| - Mooi Wel - |

|

|

| |

|

| Femke is almost eight years old. She is in group 3/4. She is an open, spontaneous child. She is doing well at school. Nevertheless she has not made any progress in reading during the past few weeks. She works hard on her assignments but she does not like reading so much anymore. Lidwien, her teacher, asks if I want to watch and listen. |

|

| |

| Femke likes me to come to her. We are sitting in a quiet corner in the classroom. I ask her to read a part from her book (Avi 3). She skips many words and twists some. Some sentences do not tally anymore at all. Yet she keeps reading on and smiles every three sentences at me. On page three I ask her to stop. We do some short games. Look for the following word…, read upside down, how many times is there the word.. She likes it and relaxes energetically. I ask her what she thinks about reading. Determined she says “boring.” “Why.” I ask. “Because it does not end well.” “You can think of another end yourself if it does not end well.” Femke smiles and whispers: “Oh, yes.” I ask Femke what she likes best at school. She says: “Writing, writing beautifully. Writing capitals because you can write those most beautifully.” In the conversation that follows she indicates more and more emphatically that “beautiful” is extremely important for her. |

| |

| I ask Femke to read the following pages of her book as quickly as possible. Tense, stuttering and correcting herself while panting she reads the page in 1 minute and 9 seconds. The following page is equally long and has a comparable grade of difficulty. I ask her to read the page but now as beautifully as possible. I emphasize that it is important that it has to be very beautiful now for me to listen to. She is going to sit leaning backwards, clears her throat, looks at me smiling, puts the book straight in front of her and starts reading. She is reading with a lovely, theatrical voice. Now and again syllables are pronounced with surprising emphasis. She is ready and looks at me beaming while I look at my watch with one eye. The performance lasted only 42 seconds. I thank her and promise to come and listen again soon. I tell Lidwien about my experience. I also tell her that Femke wants a story to end well. As far as I am concerned that is certainly the case today. |

| |

Involved in wellbeing

One colleague of mine is starting on a new course.

And the other one has adolescents at home.

One colleague of mine wants to travel for some time.

And another one has to go home at four o’clock.

One colleague of mine has a noisy class.

And another one has a polypus.

One colleague of mine has just become fifty.

And another one has two children with flu.

One colleague of mine always says he is doing well.

And another one is slimming.

One colleague of mine thinks the new language method difficult.

And another one has to travel by train for one and a half hours.

One colleague of mine is rebuilding his house.

And another one would like to have another class.

One colleague of mine is in a difficult private situation.

And another one would like everything to be the way it was.

One colleague of mine is irritated by her colleague.

And another one does not agree on the new framework.

One colleague of mine thinks she earns too little.

And another one has difficulties with his father.

Being involved in the wellbeing of your team is important

but how many hours are actually assigned for that purpose?

|

| |

| Below there are definitions and signals of wellbeing and involvement as described by Laevers****. |

| |

| ****See also: F. Laevers, Working in an Experience Oriented way with kids in primary education (2004) |

| |

| |

| Wellbeing |

| |

| Children that are in a condition of wellbeing feel top to the world. The major tone of their existence is enjoying. They experience fun experience virtue from each other and the objects. They beam vitality and at the same time relaxation and inner peace. They take up an open and receptive position for everything that is coming towards them. They are spontaneous and dare to be themselves. Wellbeing is involvement with self-confidence, a good feeling of self-esteem, defensibility. The foundation is being in touch with oneself, having contact with one’s own stream of experience, ‘functioning completely’. |

| |

The signals of wellbeing

Enjoying, having fun

Relaxation and inner peace

Vitality

Openness

Spontaneity, daring to be oneself

Self-confidence, assertiveness, a positive self-concept

Being in touch with oneself

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| If children are doing well, they are better able to satisfy their basic needs. That is not spoiling but it is conditional to be able to develop well. When children are ill your only wish is that they get well. When they are healthy and fit you want them to develop maximally. It is important to see that children act from their basic needs and to know that a high wellbeing makes that possible in a pleasant way. |

| |

The basic needs

Physical needs: eating, drinking, exercising, sleeping etc.

Need for affection, warmth and tenderness: physical contact, nearness, giving and receiving love and warmth etc.

Need for safety, clarity and continuity: a predictable, orderly environment, knowing where you are etc.

Need for recognition and affirmation: being accepted and esteemed, meaning something for someone etc.

Need for experiencing oneself as skilful: the feeling really being able to do something oneself, acquiring new insights etc.

|

| |

| Need for meaningfulness and a moral value: feeling a good human being, feeling linked etc. |

| |

| |

| Involvement |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

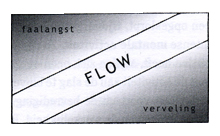

| Involvement is a condition in which children are when they are working on something in an intense way. We can tell this from their high concentration, being engaged while being engaged and forgetting time. Their acting and attitude betray an intense mental activity. They are very approachable for what the environment has to offer, they take up an open position. They feel motivated from inside to get going with an activity. The enormous satisfaction which they experience in this results form the satisfaction of their explorative urge: enjoying coming to grips with reality. Involvement only occurs in the narrow area between ‘being already able to’ and ‘not yet being able to’. Children move on the verge of their possibilities. Involvement is with all those characteristics together THE condition pre-eminently for the realization of development in the depth of fundamental learning. |

| |

The signals of involvement

Concentration

Energy

Complexity and creativity

Mimicry and posture

Persistency

Accuracy

Time of reaction

Verbalizing

Satisfaction

|

| |

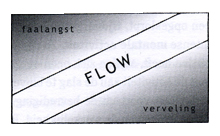

M. Csikszentmihalyi* professor of psychology at the University of Chicago, interviewed chess masters, mountaineers, dancers, basketball players, managers, teachers, mathematicians, labourers etc. He asked them about the feeling during an activity that ‘goes well’. The pattern he discovered he calls ‘state of flow’. It can be recognised by a high degree of concentration and involvement, a self-evident target orientation (you experience your acting as functional, not as leading), immediate feedback about quality (you feel the effect immediately and you can also taste the success, the impact immediately), a feeling of supervision, a loss of self-consciousness (you are not working on yourself but on the matter) and a distorted awareness of time. |

| |

| *M. Csikszentmihaly, Flow, psychology of the optimal experience (1999) |

| |

If the assignments which pupils are confronted with are too difficult or too simple it is impossible to get into the ‘state of flow’. During prolonged confrontation of too difficult assignments signs of fear of failure will appear, during too simple assignments it will lead to boredom.

|

|

|

| |

How funny it may seem: working on or having to work on too easy assignments cannot lead to involvement or to development.

|

|

|

| |

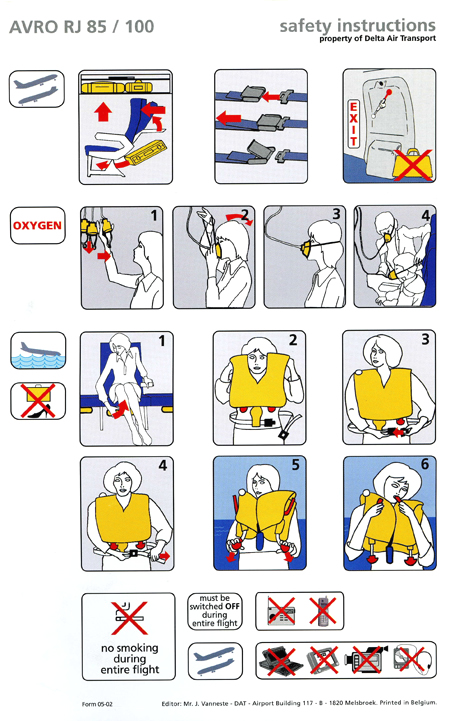

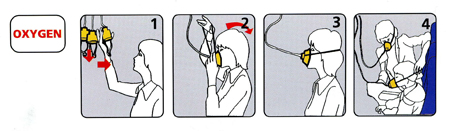

Lack of oxygen

“If in a plane the atmospheric pressure disappears the oxygen masks appear from the ceiling. First put a mask on yourself and then your children.” Or: if you do not get oxygen yourself, how do you want to help others?

If teachers are anxious about the children’s wellbeing they will have to have ‘sufficient oxygen’ themselves. A headmaster who wants his teachers to have an eye for the children’s wellbeing and involvement will also have to have this for his colleagues. And who takes care of the headmaster?

|

|

|

| |

Yes/No

During a number of lectures during which among others the use of key targets was discussed, I have polled people ‘live’.

In total there were a few thousand teachers. I asked the teachers every time to stand up if their answer on my statement was ‘yes’ and to remain seated if the answer was ‘no’.

Mostly I started with questions about the wellbeing of teachers and pupils. When I said:

“I go to my work with pleasure almost every day,”

nearly everybody stood up. At

“I go to my work with pleasure every day,”

a great number of them sat down again. At

“I know about all my colleagues how they are doing”

almost everybody looked for his chair

Typically of this item was that nearly all teachers thought of themselves that they knew all children well. At the statement:

“I know the hobbies of all the children in my class,”

nearly everybody sat down again. (In my opinion that is a very self-evident way ‘to get to know your children’.)

With reference to ‘diversity and involvement’ I stated sentences as:

‘I have visited a museum this month.’

‘I have solved an intricate cryptogram this week.’

‘I have also played my musical instrument this week.’ v

It is conceivable that at these statements only a few teachers were standing. Then I asked them what the reason was of the full to overflowing variable job responsibilities, if finally people are going to do the only things that are fit for them.

Another discussion produced the statement:

‘I have a club of peers.’

All teachers proved to have selected their friends and acquaintances outside school on for example mutual interests. Nobody arranged weekly with a club of people of the same age. An interesting, following question seemed why in education that often seemed the only criterion on which groups are formed.

It was striking that the most elementary questions about the organization of our education cannot often be answered in a simple way.

v

At the statements about competences two remarkable phenomena occurred. At the following row I stated the sentences more and more narrowly. At the first statement everybody was standing. At every following statement teachers sat down and at the last ones only a few were still standing.

‘I think knowledge of the world is important at our school.’

‘I think geography is important at our school.’

‘I think topography is important at our school.’

‘I think children should know the provinces and capitals when they leave school.’

‘I know all the provinces and capitals myself.’

‘I dare to repeat all provinces and capitals here in front of the stage.’

A few times a teacher (of a higher group) actually came on stage to perform ‘his trick’. After the applause the question remained why we are giving so much emphasis to a few (always the same) things worth knowing, which we can hardly reproduce ourselves.

Very striking was the outcome at the statements about the key targets. Almost everybody is standing up at the statement:

‘At our school we work with the key targets as guideline.’

But everybody sat down again at the statement:

‘I know 5 key targets by heart.’

Of course teachers refer to their methods. Because the publishers and the inspector explained to them that they automatically meet with the key targets if they follow the method. Still it is strange that you have no or little idea of your guideline.

The advantage of good conceptual starting points you can use them at all times.

|

| |

Would you trust a mechanic who says: “I don’t know exactly how things will work out for your car with this tool, but the manager has said that it works nicely for a lot of cars.” |

| |

The Experience Oriented attitude

An attitude of acceptance, empathy and authenticity is not only reserved for teachers who want to work in an Experience Oriented way. It is an attitude that is always important in relationships between people who respect and understand each other on the basis of equality. Acceptance of a child as a person with all its peculiarities, needs and emotions (which does not mean that all utterances of a child will be accepted) is important. The challenge is to understand and recognize what goes on inside the child and to take that into account and refer to it.

|

| |

| |

| Following pupils |

| |

| Following pupils within the Experience Oriented Education means before establishing how far they have advanced in their development establishing if children are developing. If children are developing is of course derived from the level of involvement and wellbeing which they averagely show. |

| |

| For kids the Process Oriented Child following system has existed for a long time. Of a more recent date is the Process Oriented Child following system for the entire primary school. Various possibilities have been included which can contribute to preventing problems in the area of wellbeing and involvement. Moreover in a first group screening the level of competence is considered and screening lists are to be filled out for different subject and education areas. |

| |

| |

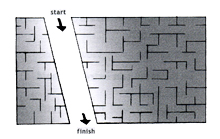

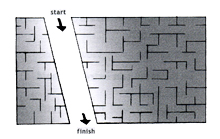

| Quite a puzzle |

|

|

| |

|

| Jan asked me to go with him and have a look at Tijn (5 years old). Tijn ‘does do everything’ but there is no real involvement. And so his development is probably not optimal. |

|

| Tijn is making a self chosen puzzle. I am sitting down next to him. Tijn smiles at me and says: “Easy.” When he has finished he wants to walk away. I ask him if I may make the puzzle more difficult. “Okay,” Tijn says and smiles again. |

|

| I take the pieces of the puzzle, shuffle them and put them upside down on a pile. “Take them one at a time and put them down correctly,” is my instruction. Tijn starts and soon reacts with “I can do it.” When he has finished and I have made him compliments I ask if he can put them in the right place in one time. Tijn starts again and puts two pieces in the right place. That he knows ‘for sure’. The third piece he is shoving up and down. |

| |

| Finally he asks me if he can keep that piece for a while. I am glad about his strategy but only indicate that that is okay. When he has finished the puzzle he asks if I can do another one also in that way. Beforehand I ask him to have a good look at the puzzle. We ‘anchor’ a number of important points in the puzzle. He is incredibly proud that he succeeds again. Immediately he takes the next puzzle and starts without ‘anchoring’. Already at the second piece he finds out that he does not know what the representation looked like. His impulsive behaviour probably proceeded from the thought ‘that is important for me.’ He looks at me inquiringly. I look back at him inquiringly. “I must look first,” Tijn says. “Of course”, I say. When Tijn has succeeded he asks momentously: “Can you make it even more difficult?” I take two puzzles and shuffle them mixed up. |

| |

| I do not say that it will probably take a long time and walk away. After several minutes he stands in front of me and smiles: “Come with me.” Of course the puzzles are on the table as intended. “And now?” Tijn asks. “No….,” I say “that will take a whole morning’s work.” “Go ahead,” Tijn says. I take a tray and shove all puzzles of the classroom into it one at a time. Tijn’s head becomes redder and redder. “I can do it,” he cries. “How do you think you are going to do that?” I ask. “I will put all boards ready and I will take every piece first that belongs to a puzzle.” “Jan,” Tijn says “do come over here. Tomorrow this will be my office and nobody may disturb me.” “How will you communicate that?” Jan asks. After school Jan makes a ‘traffic sign’ together with Tijn with a child and a cross though it. Tomorrow the puzzle office will be for Tijn only. |

| |

| |

| Five involvement increasing factors* |

| |

| * See also: F. Laevers, Working in an Experience Oriented way with 6 to 12-year- olds in primary education (2004) |

| |

| Whoever endorses the statement that involvement is important for a maximum development must be able to create as many moments as possible which meet this. Every activity has a higher chance of real success if you take into account a number of approved factors: |

- A good atmosphere in the group and mutual relationships which are relaxed and development promoting. It is important that children feel safe and accepted.

- Working at the level that a child can cope with and that challenges at the same time. Children must feel the challenge for activities. However, that does not mean that education has to be completely individualized.!

- Work that is close to reality and therefore interesting for children. Activities that concern the children’s world of living and perception are experienced as meaningful.

- The possibility to activity, doing actually something oneself. Children cannot listen for a long time. All kinds of things must be going on. Calm and activity need not be in each other’s way!

- The possibility to take own initiative. It is about children appealing to their developing potential. For this they must get their own options.

|

| |

If the involvement is low, for instance in arithmetic, it is important to think over all involvement enhancing factors and to influence as many of them as possible in a positive way. |

| |

| In order to pay attention to the five involvement enhancing factors you can use a view guide (see appendixes). |

| |

| From the five involvement enhancing factors it is self-evident that it is about interaction: doing and talking (about it). This is confirmed by research. Filip Dochy** examined the amount of retention of activities. From research it seemed that retaining experiences and remembering knowledge is defined by the kind of activity. |

| |

Listening to explanation : 5%

Reading : 10%

Processing information : 20%

Demonstration : 30%

Discussion groups : 55%

Practising : 75%

Performing in reality and explaining to others: 80%

|

| |

| **See also: F. Dochy, Assessment in education (2002) |

| |

| The Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky confirmed this outcome with retrospective effect. He said: “The structure of the language is not simply the reflection of the structure of thinking. Therefore we cannot consider words as the clothing that is put around the thought. Language is not just a form of expression of elaborated thoughts. Thinking is restructured when it is put into language. It is not expressed but it is completed in the word.” |

| |

| He states that the conceptual system of a human being has a direct influence on the way in which he thinks about the world and experiences it. He gives a good example when he shows that cultures with different languages experience the world literally in a different way: We have one word for snow, while the Eskimos know many words for it. Because Eskimos can distinguish in a much more detailed way they ‘see’ snow literally different. Thus Vygotsky reaches the conclusion that growing up in a specifically linguistically structured environment leads to the child starting to see the world not only through its own eyes but also through its talking. Later it is not only the seeing but also the acting that is formed by words. |

| |

| |

| Five ways of working full of opportunities |

| |

| By working on the five involvement enhancing factors teachers can try to increase the children’s involvement within the structure of a (classical) programme. At a certain moment the conclusion can be that it yields insufficient result. Then you can benefit from ways of working with which you can better meet what children need. |

| |

| From the Experience Oriented Education five ways of working full of opportunities have been described which result from the five involvement enhancing factors. The ways of working are not new. Some have found their way into other educational concepts – sometimes under different names -. It is important to keep in mind that education does not become Experience Oriented by applying ways of working. However, they can help. The children show themselves if you succeed in your intention. |

| |

| The five ways of working are: |

- ‘Circles’ and ‘Forums’ (or celebrations) proceeding from the factor ‘atmosphere and relationship’.

- ‘Contract work’, proceeding from the factor ‘working at the level’.

- ‘Project work’, proceeding from the factor ‘closeness to reality’.

- ‘Workshops’, proceeding from the factor ‘activity’.

- ‘Free choice’, proceeding from the factor ‘own initiative’.

|

| |

| For the lower classes 10 points of action have been worked out which will influence the current practice in a positive way. |

| |

Point of action 1

Rearranging the classroom into corners.

Point of action 2

Dealing with the filling out of the corners thoroughly.

Point of action 3

Bringing in new materials and activities.

Point of action 4

Discovering interests and thinking of and offering connecting activities.

Point of action 5

Giving involvement enhancing impulses during activities.

Point of action 6

Extending initiative and supporting it with rules and agreements.

Point of action 7

Exploring and improving the relationship with every child and among children.

Point of action 8

Offering activities which help children to explore emotions, values and relationships.

Point of action 9

Helping children with emotional problems with directed interventions.

Point of action 10

Helping children with specific developmental needs with directed interventions. |

| |

| |

| |

| Not or but and |

| |

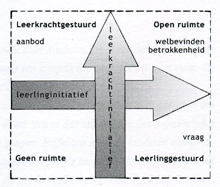

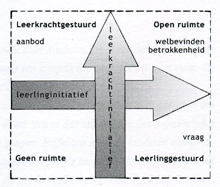

| Where is the Experience Oriented Education now? How do wellbeing and involvement relate to each other? Where does the teacher stop and where does the pupil begin? |

| The Experience Oriented Education is in ‘the tension’ of two forces. It is not teacher or pupil driven; it is teacher and pupil driven. It is not demand or offer oriented; but it is demand oriented within a good offer. It is not process or product oriented; it is maximum attention for the process to get the product as excellently as possible. It is not with attention for wellbeing or involvement, it is with (alternating) attention for both. |

| |

| |

| Challenge and balance |

| |

| There is a contradiction which complicates the counselling of developmental processes. On the one hand the organism and its development exist by the grace of its being challenged: involvement. On the other hand that same organism is focussed on wanting to be ‘in balance’: wellbeing. There is an alternating tension between wanting to be challenged and wanting to be in balance. |

| |

| An example |

| Children who are playing are challenged by their environment. The environment asks them questions which they answer with all their being. The interaction with the environment literally brings them in unbalance. The discoveries take children further in their thinking and acting. However, by nature the body is also aimed at restoring the balance. |

| |

| The phenomena ‘challenge’ and ‘balance’ make the necessity visible to view processes. It is of vital importance that children are challenged and it is of vital importance that children can get into balance. However, it cannot happen at the same time, let alone in class. |

| |

| The more flexibly these two phenomena can form from the organism the more self-evidently children can develop. The question is how much space there is to be really challenged and how much to be able to get really into balance. Can children become involved because they are really challenged? And when they are involved can they keep this ‘state of being’ or is it interrupted by the schedule? And is there a place where children can quiet down? |

|

|

| |

|

|

| Remarkable for an open space where wellbeing and involvement are high is that teachers and pupils control their way of working. Teachers take care of a good offer and pupils take initiatives. Within this kind of educational contexts it is not clear at a certain moment who is driving. Demand and offer can come from as well teachers as pupils. Then the ‘state of flow’ becomes visible and tangible. |

| |

|

|

| The open space is the place where pupils and teachers have to learn from each other because they make discoveries inside and outside themselves. It is the place where the tension is maximal where everybody feels that things are learnt. The tension between teacher and pupil, between pupils mutually, between demand and offer, between process and product, between wellbeing and involvement. |

|

|

| Those are moments when everybody becomes aware that it is ‘a near thing’. That is only possible because of the interaction with each other and the environment. Learning does not go without conflicts, it does not go smoothly, it does not go by merely looking on. Learning is exciting, very exciting! |

| |

A teacher in secondary education stuck to his ‘own way’ of working.

He covered the blackboard with chalk.

His students did not write with him,

but asked him to move aside a step,

so they could take a picture of it with their mobile phones.

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|