| 8. Developing personally justified |

| |

|

|

Developing personally justified is important in order to deal durably with ‘people’. Man will have to do well, if we want to expect something good from man. Durability becomes an insight in a personal sense that looks at man from inside and outside. |

| |

| As an introduction to this chapter I give the assumptions that precede this description. |

| |

| |

| Assumptions: |

| • Everything is interaction |

| There is a continuous, very complex interaction between every organism and its environment. That is the way at subatomic level, but also with cells, with humans, with organisations, with countries…. |

| • Everybody does as best as he can: otherwise he would do things differently |

| Taken into account all factors, the organism is aimed at surviving/living as well as possible. No matter how unimaginable behaviour can be for other people. |

| • You can influence relevant values; you cannot have the disposal of them |

| It is important to distinguish between matters that you can influence and those you cannot influence. Special phenomena such as well-being, involvement and linkedness can be influenced. But you cannot have the disposal of them. You can try for instance to please others but you cannot determine if it makes somebody happy. |

| • Every person is unique. Differentiation is a matter of fact. |

| Because even identical uniovular twins have their own life-path, there is nothing so dishonest but treating everybody the same. |

| |

| |

Jos Kessels writes in ‘Free space’: “Man falls right in the middle of things (in media res) when he is born. And in ‘the middle of thing’ he falls out of it again. People are always in the middle of something. In order to give sense and meaning to that situation, they need an idea of coherence and direction. That is why they think of consciously or unconsciously a beginning and an end to it. They make a story to it.”

|

| |

| Trying to answer the question ’when am I doing right?’ is very pretentious. Yet it is the question that occupies professionals. I have often asked the question to school-teams: “Who of you does worse than he can?” Nobody. Everybody does as well as he can otherwise he would do things differently. Yet it is true that some strategies have a better effect than others. |

| |

| |

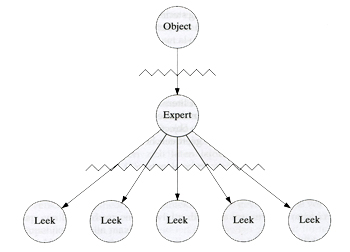

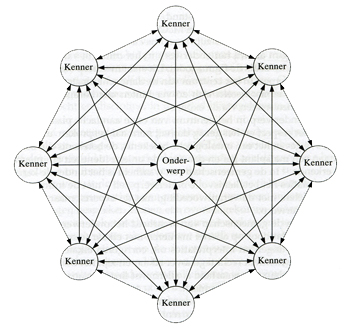

| Interactive community |

| Palmer wrote in his book ‘Teacher with heart and soul’: ‘Physicists have shown in a series of important experiments that subatomic particles behave ‘as if a kind of communication exists between them.’ These so-called particles, widely scattered in time and space, seem to be connected with each other in a way that makes them not behave like separate individuals, but as participants of an interactive and mutually dependent community. |

| |

| The fact that at a subatomic level the separate parts are dependent of each other and of the interaction that connects them, is important for a translation to the educational context. There is another essential statement that gives insight into the way in which the person who knows and he who is known influence each other. |

| |

| |

| He who knows and he who is known |

| A characteristic of development (what was enveloped becomes developed) is that the system changes and that the borders move with this. It is familiar that he who knows and he who is known have a relationship. |

| |

| Palmer: “Physicists are not able to study subatomic particles without changing these during their research. We cannot keep up any longer that there is an objectivist gap between the world ‘outside’ and the observer ‘inside’ as pre-modern science states.. He who knows and he who is known are linked to each other and every statement about the nature of he who is known reflects also the nature of he who knows. That interaction is not linear, static or hierarchic. It is circular, interactive and dynamic.” |

| |

Everybody who counsels kids or adolescents knows the pedagogic phenomenon of diverting borders of changing systems.

|

| |

| Who works with people, knows it. People are no objects but subjects. The influence each other and interpret the other person’s behaviour, starting from a personal view or taste. Man behaves with another person in a way, in which he manages intuitively best. The other way round it is also true. A multiplicity of factors determines which abilities are appealed to and which behaviour is shown. |

| |

| People influence each other and so they react to every person differently. Everybody knows: ‘I can do this with him, but not with her.’ |

| |

When a counsellor says a child is troublesome you do not know anything about the child. Then you know that the counsellor thinks the child is troublesome.

|

| |

| |

| Being and acting are one |

| We influence each other but we interpret our own perception. Our acting is direct and is prompted by who you are. |

| |

| In ‘Ethical Know-how’ Varela writes: “You react as a counsellor directly from your perception of the situation, not from the reflection on the situation. You react as a counsellor in the first place as a person and so the children will know you too. Not as a qualified didactician, coach, internal counsellor, remedial teacher, more knowing partner, teacher or process counsellor (from competences) but as an authentic individual (from authenticity). Counsellors work here and now in a direct and spontaneous interaction with their environment. There is an immediate relationship with the environment, in which you cannot think for a moment: in which you have to know right away what you must do (and you do it). You react you’re your experience of the situation and not from reflection on the situation. The answer to the question of counsellors ”when am I doing well?” could get a counter question: “Who are you?” Not because everything is good but because the being and acting of the counsellor are one. ” |

| |

A pilot who sees just too little may not fly anymore but a teacher who sees almost nothing….

|

| |

| |

| We teach who we are |

| With regard to the issue of competences which you should have as a teacher professor Stevens says in this respect: “Ability is who you are. That does not make competences superfluous but less interesting.” |

| |

| Palmer describes that phenomenon as “We teach who we are.” |

| |

Is the interaction okay

Then the development will stay

|

| |

If we teach who we are it makes a difference who we are. And professionally it also matters what you prefer, but for instance also what you hate.

You must be able to stand tears

Carina counsels a starting group. In a beautifully furnished classroom eight kids are playing who are just at school. The group will grow quickly. Carina asks me to look at Mento, a boy that have occupied the feelings from the first day. He is troublesome, pushes, hits, cries loudly and often runs through the classroom. The other children are visibly afraid and do as he says. Mento is hardly approachable. Carina says that it looks very much like ADHD. She hardly dares to say it. For he has only been at school for a few weeks. But she does not find an entry to influence the behaviour in a positive way.

When I come in I do not have to ask who Mento is. He runs, climbs onto the couch, across a chair, through the window of the dolls’ corner and meanwhile he orders his classmates about. When Carina does not think it is responsible anymore she calls the children into the circle. Mento jumps onto the back of the couch and averts his head. He does not want to hear what his teacher has to tell. When she speaks to him, he turns around and is going to lie on his belly in the corner of the couch. When Carina grabs him he starts crying and beating. Somewhat later all children are playing again and Mento is walking through the classroom again.

We make a quick reconstruction. Mento’s well-being is bad. He does not want to be talked to about his behaviour and he certainly does not want to be seized. Carina indicates that she has troubles with his aggressive behaviour.

We let Mento walk till he takes a helmet from Sjoerd. I seize him and tell him that he may not just take the helmet from someone. I take the helmet from him and give it back to Sjoerd. Mento walks to his chair and starts crying. Carina is shocked and walks away. I ask her what is the matter. “I cannot stand it when children are crying” , she says. I tell her that Mento feels unpleasant from inside. In his behaviour that he displays towards other children, that prickly behaviour is confirmed. His classmates cannot offer counterbalance. So it is necessary that he runs up against ‘the border’. Of course it startles him and he starts crying. Crying is not an utterance of sadness here but of freeing himself of the feeling of incompetence. He finishes the awkward experiences that are in himself while crying.

While Carina and I are talking we see that Mento sometimes looks up to the other children. In the meantime Sjoerd has put his helmet on the floor and has walked away. After some ten minutes Mento gets up, looks around and walks into the classroom. He is going to sit with five children that are painting. When he has been looking for some time he takes a piece of paper and is also going to paint. He pulls a tray with paint towards him. “No”, Suus calls, “that must be in the middle. Then everybody can take from it.” Mento shoves the tray back into its place.

|

| |

If you do not see the butterfly in the caterpillar,

If you do not see the bird in the egg,

What do you see in a child then that troubles you? |

| |

| We ask the what, how and why- questions but not the relevant who-question. Children do not recognise the person as a counsellor in the first place. They experience the person who hides in the cover of his function. And that is somebody you like to get along with, somebody who ‘does not disturb you’ or somebody who you do not like so much. The way in which the contact is built up determines the extent to which the counsellor can use his educational contents. |

| |

| Children ‘know’ immediately if you mean what you say: they feel very quickly if you are real and they react accordingly. The personality of the counsellor is the decisive factor at every level. Good counselling cannot be reduced to technique but results from the identity and integrity of the counsellor. |

| |

| It is pleasant for children if the counsellor takes up a vulnerable and available position. That means that we will have to talk with each other about our innermost. That seems risky in professions that are afraid of looking for the personal element and safety in technique, distance and abstraction. |

| |

| |

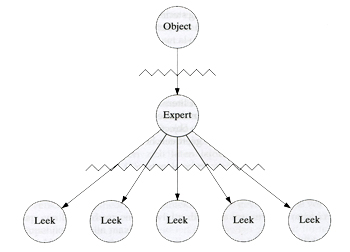

| Passion keeps you away from your pitfall |

| Some counsellors only want tot transmit objective knowledge. They restrict themselves to the facts and are not influenced by their own feeling or prejudices. The pitfall of this is that the objectivism is so obsessed by protecting pure knowledge that children may not have direct access to the object of study. Other counsellors state the child is the standard. But if children themselves are the standard it is difficult to fight ignorance and prejudices with individual children of the group. |

| |

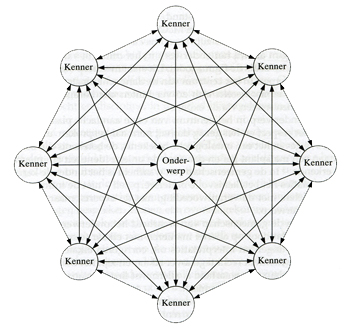

| In order to have the counsellor fulfil his share usefully and give the children autonomy without the individual becoming the standard, a third factor is needed that ‘is above the parties.’ It is the subject of learning, it is passion for a subject. Because passion for the subject puts the subject in the centre of the learning cycle and not the teacher. |

| |

|

| From Palmer: Teacher with heart and soul |

| |

| And if the important subject is in the middle, the pupils have direct access to the energy of learning and living. In this way the teacher can be a narrator of historic tales with passion but he can also explore an new area of research practically ignorant and with much interest. But then we are not there yet. |

| |

Your body is not only made to take your head from one meeting to the other.

|

| |

| |

| Basic needs |

| If children are doing well they are better able to satisfy their basic needs. That is not spoiling but it is conditional to be able to develop well. When children are ill, your only wish is that they get better. When they are healthy and fit you want them to develop maximally. It is important to know that children act form their basic needs and to realize that a high well-being enables this in a pleasant way. |

| |

| Professor Laevers distinguishes the following basic needs: |

| |

| • Physical needs |

| Eating, drinking, exercising, sleeping etcetera. |

| • Need for affection, warmth and tenderness |

| Physical contact, nearness, giving and receiving love and warmth etcetera. |

| • Need for safety, clarity and continuity |

| Predictable, orderly environment, knowing where you stand etcetera |

| • Need for recognition and confirmation |

| Being accepted and respected, meaning something for someone etcetera |

| • Need to experience oneself as skilful |

| The feeling of really being able to do something, gathering new insights etcetera. |

| |

| If one or more basic needs are not satisfied it can affect a person’s complete functioning. |

| |

Getting to know by fulfilment

What is more beautiful than being allowed to become who you are. Everything that is yours is ready within yourself. It must open and get the chance to grow to maturity. Or as poet R. Kopland put it beautifully in ‘Memories of the unknown’:

“The first kisses I got from a girl (…) penetrated into the far corners of body and soul. Something was ready of which I did not know that it was ready and there was a longing that I got to know by the fulfilment. ”

|

| |

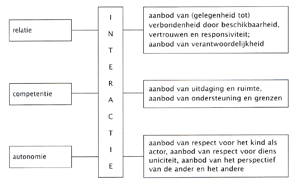

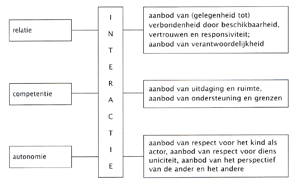

| In his publication ‘Feeling like school’ professor Steven introduces a basic model in which he formulates the pedagogic answer to ‘his’ basic needs. The coupling can only be made by interaction. |

| |

|

|

|

| From Stevens: Feeling like school |

| |

| |

| When good is not sufficient |

| When the counsellor puts the subject in the centre of the learning circle and not himself and if he takes into account the (basic) needs of children then it is the quality of the interaction that matters. Then the question arises: “What is good interaction?” and “What do you do if a child is not doing well (well-being) in spite of your efforts and/or does not develop well (involvement)? ” If it is about the answer to the question: “What is good interaction?” professor Laevers bases his case on among others Rogers. |

| |

|

|

With the ingredients of Rogers he describes the Experience Oriented dialogue as one of the pillars for his concept. |

| With regard to the question: “What do you do if a child is not doing well (well-being) in spite of your efforts and/or does not develop well (involvement)?” he derives support from a powerful description of Grendlin. First Rogers… |

| The Experience Oriented dialogue is an empathic way of communicating. That conversation is aimed at the experience stream of the other person: on ‘that what goes on inside the other person.’ Rogers analysed communication into three aspects: acceptance, authenticity and empathy. Of course not every conversation has to be held with attention for these aspects. Sometimes it is good or necessary to reject, to ignore or to communicate from your own perspective. But if you want to become affiliated to the needs that children really have attention for acceptance, authenticity and empathy are evident. |

|

| |

|

|

Zidane |

During the finals of the world championship football in Germany in 2006 the French star Zinedine Zidane gave a head-butt against the chest of the Italian Marco Materazzi.

Some thought the status of Zidane as a world football-player was unassailable: acceptance.

Others were very much shocked by the incident: authenticity.

Again others could only imagine after they had heard what the Italian had said: empathy. |

|

| |

| |

| When are you doing well? |

| A first answer to the question: “When am I doing well?” I want to give with reference to an example from practice: |

| |

| During an educational in content meeting a teacher brings in a case referring to a talk about the Experience Oriented dialogue: “This morning I was sitting near a child who had made a drawing. He asked me to write something to his drawing and dictated: ‘The thieves are going into the machine. They must all be cut into pieces. Then blood is coming out.’ I was so shocked that I did not know what to do. What would you do?” Karin says: “I would write it down. It is the child’s story.” “I would be shocked too,” Peter-Paul says. “I would let him feel that I was very shocked.” “I would be especially curious why he is drawing this and what is on his mind,” Tina remarks. We do not wonder who is right and what is the best intervention. We are looking at the aspects of the Experienced Oriented dialogue and we state a number of striking elements: |

| |

| Karin aims especially at acceptance; she takes over as a matter of fact what the child contributes. Peter-Paul intuitively shows his authenticity; the child can tell from his reaction how it ‘enters’ him. Tina feels empathy; she is aiming at what happens inside the child. |

| |

| The three aspects of Experience Oriented dialogue acceptance, authenticity and empathy seem to get priority in these interventions in a natural way. Each teacher reacts intuitively rather from one aspect than from another. |

| |

| Then the question does arise: “But what is the best intervention now?” Again it does not seem useful to judge from good-bad, let alone that (universally) the best intervention could be pointed out. Everybody has a natural way of reacting, which inclines strongly to one aspect of priority. But because everybody thought his own intuitive aspect important, the insight developed that the boundary of that aspect should be defined by the other aspects. Or: it is wonderful that Karin reacts from acceptance, but it is important that she is conscious of her own authenticity and the interest for “what is going on in the child’s head.” It is excellent that the child sees what his story does with Peter-Paul. However, Peter-Paul should try to keep attention to ‘how this enters the child again.’ And of course Tina may be interested in what happens inside the child’s head. But she should take care that the child can tell from her reaction what his story does to her. |

| |

| We put Karin to the test. We make up some sentences that she would definitely not write down on the drawing. She notices that there is indeed a limit to what she would write down gratuitously; a limit to her acceptance. She feels that authenticity and empathy are ’at play’ then as a matter of fact. |

| |

| |

| The first answer |

| The first answer to the question: ’when are you doing well? ’ could be referring to the interaction: if you take into account acceptance, authenticity and empathy. It is good if you know your (intuitive) aspect of preference and it is important that you can justify the aspects which appeal less to you by nature. |

| |

| • A counsellor who has been really authentic, but for example so angry that he could not feel empathy for the child, is not left with a pleasant feeling. |

| • A counsellor, who feels so empathic towards the children that this is at the cost of her authenticity, does not persevere very long. |

| • A counsellor, who is extremely aimed at the acceptance of children, is sometimes unable to feel empathy and to overlook the consequences for others. |

| |

A child that you take home inside your head with you has put acceptance, authenticity and empathy out of balance.

|

| |

| |

| Not and but in |

| The second answer to the question “”When am I doing well?” with reference to the issue: “What do you do if a child is not doing well (well-being) in spite of your efforts or if it does not develop well (involvement)? ” is introduced by a description of Grendlin: |

| |

|

|

“An ecological approach makes it possible to penetrate in the process of giving meaning to the level of the experience of ‘felt confessions’. It is the experience stream where the perceptions, images, memories, fantasies and thoughts get a shape in order to constitute the ‘affectively experienced situation’ together with the feelings. In one to the utmost performed act of empathy – at which one ‘becomes’ the other person – one reaches the sharpest possible vision of what reality looks like for somebody.” |

|

| |

Empathizing

Assignment: There are ten birds on a branch. A hunter shoots one of them. How many remain seated?

Those who can do arithmetic are inclined to answer ‘nine’.

Those who can imagine the situation know that no bird will remain seated.

|

| |

| Of the moment, at the moment |

| |

|

|

|

|

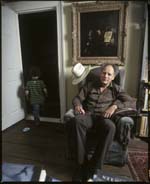

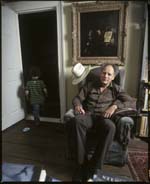

Photographer Duco the Vries makes beautiful portraits. He published ‘Bikers in Holland’, a special book in which he photographed meeting, the home situations, the marriages and the funerals of motor club Rogues MC.

Many famous and less famous Dutch persons have been portrayed emphatically and typically by him. His philosophy is clear: “I cannot photograph anyone if I do not know how he is doing. The feeling of the moment is important. I often talk longer than that I take pictures. There is a picture of Cruijff who is looking at his watch. He did not have time to be photographed. That photo is right! You cannot take a picture of a quiet, relaxed man in such a situation ” |

| |

|

|

|

|

Duco is also a teacher at the photo academy in Amsterdam. He regularly gives his students the assignment that they have to take three different portraits of a person in one hour. “Some students come in and just shake hands with the ‘photo object’ in order to look for a good spot and good light. That cannot be anything because the person is only put in a beautiful environment. |

| |

|

|

|

|

The students that lose themselves in the model know to change small important nuances, because of which the photo of the moment, at that moment is completely good. A portrait has to be more a less a reflection of the feeling of the meeting. And not for instance a photo that you have devised before and which you try to make on the spot. Being open for the moment is most important. So somebody who only shakes hands with his ‘model’ and has no further attention for him before he starts photographing, does not do justice to the other person but in the first place he does not do justice to himself. ” |

|

| |

| |

| Construction and re-construction |

| From the constructivist vision it also becomes visible what you can do if the development gets stuck. If the developments have gone well the construction is visible. If developments get stuck there is a self-evident step: the re-construction. Reconstructing means rebuilding, re-composing. You try to imagine what happens inside the other person. You try to penetrate to the deeper meaning of behaviour. From there new possibilities can become visible. |

| |

| An elaborate description can be found in Experience Oriented Education; from orientation to implementation (van Herpen 2005). At reconstructions you must (sometimes intuitively) guess what children do already know and can do and what they do not know or cannot do (yet). But it is also important to ask yourself if children do not ask something different with their question. A number of examples: |

| |

| A language example |

| Marlis (9 years old) comes to me with her text. One of the words she has written is: ‘stambeelt’ (statue). I tell her the word has not been written correctly and ask her if she wants to change it. I tell her that it is ‘stand’ and not ‘stam’. She did not know that so I do not let her guess. I do ask her if she has any idea why it is ‘stand-beeld’. She says: “Certainly because it is standing.” I wink at her. |

| Then I say that ‘beelt’ should also be different. She does not react. I ask her if she knows when you write a ‘d’ or a ‘t’ at the end. “Making it longer,” she says, “oh yes, a ‘d’ of ‘beelden’.” I ask her to write down five words with a ‘d’ and five words with a ‘t’ at the end as quickly as she can. She starts immediately. |

| |

| An arithmetic example |

| Stijn (10 years old) tells me he does not know the table of 7 very well. “I think it is difficult,” he says, “more difficult than the others.” “Which others?” I ask. “Well, I think those of 1, 2, 5, 6, 9 and 10 are easy.” “Why is that?” I want to know. “Well 1 time is 1 time, 10 is with a nought added, 2 times is 2 times, 5 times is half of ten, 6 times is one time more than 5 en 9 times is one time less than 10.” “That is a clever reasoning,” I say, “but if you know that you will only have to learn 3x7,4x7, 7x7 and 8x7.” Stijn walks away, writes them one under the other and he fills in what he already knows. Then he quickly calculates the four remaining sums and practises them. Then he comes to me with the information that he knows them. I ask them in order and mixed-up. He sometimes falters for a moment at the four new ones but ‘does know them’. In the afternoon I ask them again: during lunch, when playing outside, during project work. When I ask them again in the changing-room of the gym a few days later, he still knows them. “Easy as pie,” he calls. “And how you must learn a table is something you learnt from me,” he says proudly. He is right. |

| |

| A social-emotional example |

| Rasa (8 years old) says she thinks arithmetic is difficult. “I do not understand it at all. I really do not know what I must do.” This morning she entered the classroom silently. I have not heard her all morning. She behaves differently from other times but I become aware of it that moment. She comes and sits besides me. “What did you do yesterday?” I ask. “Why?” she says. “Well, your sister came to fetch me and you had to leave quickly.” “Oh yes, we had to go to an aunt and there…” |

| And there the situation seemed different from usual. The family was concerned about an ill cousin. Her mother had cried and she did not exactly know what was the matter with her cousin. She tells me everything she knows and what she does not know. Then she is leaving again. She walks to her table and starts doing arithmetic. |

| |

| An example from the gym |

| Fenna (11 years old) is a shy and withdrawn girl. During tag she allows herself to be touched first as a frightened little bird. “Yes, it is no fun like that.” Cas shouts, “You must join the game!” But Fenna does not want to join the game as Cas wants her to. I see that Fenna huddles up when they walk into her direction and thinks there has to be a protecting space around her, before she can be touched. I have two trapezes put upside down in the gym. In each trapeze there may be one child. We play another game and when I call two names, they must touch the two children in the trapezes without getting into that space themselves. When I let Fenna sit down in one of the trapezes, initially she remains in a corner. Cas is interfering again. “No, you have to jump to the other side, so that they cannot touch you.” His instruction seems to work. The space is safe enough and every tagger she got freer. After some time she enjoys she cannot be touched. |

| |

| Examples from: ‘Experience Oriented Education, from orientation to implementation’ |

Do you pass a judgement or take the advantage?

|

| |

We need counsellors who can act quickly, intuitively and adequately. The theory is clear but the practice five little time for consideration……

Cell-phone instead of protocol

A pupil from secondary education was killed in a traffic-accident early in the morning. The headmaster told me that formerly in such a situation he went to his office with the management-team. There it was determined what they would undertake successively from the protocol that had been drawn up. But in these day the fellow students who are on an excursion abroad hear it sooner via sms than the teachers who are with them. The internet spreads the news already, sometimes before the complete family has been informed. So you need teachers that will react intuitively well. The values of the school must be translated directly into clear, good interactions when it comes to it. Pupils know exactly which teachers can do this well and credibly.

|

| |

| |

| The second answer |

| The second answer to the question ‘when are you doing well?’ with reference to the interventions on children who get stuck is: make a reconstruction of a child who is not doing well and/or who is not developing maximally, preferably with colleagues to reach as many points of view as possible. Think on account of that reconstruction of interventions which can put the child back into process and execute these. |

| What next? |

| Then you are doing well; as well as you can! |

| And what if the child still does not become happy then or still does not develop? |

| Then you make new reconstructions (or with other people) and try other interventions. |

| And what if the child still does not become happy then or still does not develop? |

| … |

| There can be a moment that you conclude in consultation with parents and colleagues that a child (with all that it is and to which it is exposed) cannot be happy or develop maximally in your setting with you as counsellor. The worst thing that can happen to such a child is that this cannot be discussed. Some councillors are ‘very worried’ or ‘do not even sleep anymore’. Is this to the child’s benefit? |

| The child will benefit from a maximum effort. In return a councillor must be able to do his work with as few irritations and frustrations as possible. And that chance is biggest if he knows every day that he has tackled things seriously and with the best intentions and that he has done what he could and that that is the highest attainable. And there will be another day tomorrow. And that, no matter how badly you wanted it, you are not able to make everybody happy. |

| |

| That counsellors are not able to make everybody happy or to have everybody develop maximally does not sound very optimistic. On the other hand it is good that counsellors who dedicate themselves to the matter with heart and soul can bear up against sometimes turbulent times. It is so important that you feel you are doing this together. That is why the tuning talk about vision and the choice of point of view of concept is important. The child will have to be the compass, but you can ‘do well’ if you feel you matter: because you practise your job with passion. |

| |

The maximum realizable

Counsellors often give as reaction on the pressure of work that they are so perfectionist.

Perfectionism is striving for perfection.

It would be good if they strive from a realistic perspective for the maximum realizable.

|

| |

| |

| The most important answer |

| Maybe the most important answer to the question ‘when are you doing well?’: “If you have confidence!” Confidence in yourself but especially confidence in the power of children. Children often know very well what is necessary and you may join the trip. Take care you are near the wheel when the weather forecast is bad, but be surprised if you see where the children are taking you. |

| |

| In order to support the confidence in children and the fact that they are well able to give you the insights that are necessary, a kind of story before going to sleep. Or rather: a little sum before going to sleep. |

| |

| |

| A little sum before going to sleep |

| “Good night, Sophie ” |

| “Marcel?” |

| “Yes?” |

| “Do you want to assign me a sum?” |

| “Why?” |

| “Well, I think that is fun.” |

| “Okay. Eh, 248 and 248.” |

| “That is 200, 400, 480….496.” |

| “Good. 123 and 362.” |

| “Eh, 400, 480, 485.” |

| “Well-done.” |

| “Yes I get such sums if I have made the rest well.” |

| “What do you mean?” |

| “Well, I have to do the work everybody has to do and if I have done that well, then I will get a paper with very many sums and I may do those.” |

| “Nice.” |

| “But I do not always know how I have to do the other sums well.” |

| “Those are much easier than these sums.” |

| “Well, then I understand it for example when the teacher explains it and then I read the assignment once again and then it says that you have to colour beads and then there is a white ” |

| “How annoying.” |

| “Yes…. Good night” |

| “Good night” |

| |

| She is almost six years old and she already understands quite a lot. But I wished she had invented this. |

| |

| |

| Labelling negatively |

| Some counsellors ‘do not sleep anymore’ if children are not doing well or do not develop well. This is of no use to children. You had better sleep and be fit at work in the morning. If those children are examined and they are diagnosed as: retarded, dyslectic, ADHD, PPD NOS, then those counsellors feel relieved from a burden. Their expectations diminish and… the children are going to adapt to that (low) expectation (Pygmalion effect). It is better if you always look at the reality what is possible and put the goal at ‘the highest possible level for the child’. |

| |

| Understand me well: if children need a special care on the basis of a disability or disturbance then it is not right not to give them those but equally not right to lower the expectation if the ceiling of children that ‘are different’ has not been reached. |

| |

| Labelling can be explained positively and negatively. Positive in the sense that you should know about children as precisely as possible what they need and negatively it it leads to exclusion and lowering of expectations. |

| |

| |

| Labelling positively |

| I would rather use ‘labels’ to have counsellors to typify themselves. In other words: to every institution, to every organisation, to every counsellor a label could be attached on which could be read what you may expect from it. The durable educators make their values known and live accordingly. Children may expect that from them. |

| |

An example of labelling positively

Kuyichi ia a line of clothing that is aimed at making and selling honest jeans and other clothing. Starting-points in this are the three aspects of socially durable enterprising: social, environmental and economic. The view of Kuyichi is that clothing has to meet high standards of quality and fashion for, according to Kuyichi, you then only sell a Fair Trade product in the normal clothing retail trade. The circle in the logo represents the world and the plus sign points to positive.

The Peruvian cotton farmers earn a normal salary for their harvest thanks to Kuyichi. They get a guaranteed minimum price for the grown cotton despite the fluctuations of the price on the world market.

The make of fashion Kuyichi is an initiative of the oecumenical developing organisation Solidaridad.

On the labels in the clothing can be read:

Kuyichi is a style conscious, a simple concept, create style and be conscious of how we create it. It’s a concept we have been working with for years developing organic cotton in fair working conditions, respecting the environment, being relevant and sexy, and why not? Being dedicated to better manufacturing doesn’t stop us creating relevant fashion for tuned in customers. It’s a look good / feel good situation. This is just common sense. This is Kuyichi.

|

| |

| Labelling positively is not sufficient if the confidence in each other is not built up. |

| |

| |