| 12. A perspective for depressed youngsters |

| The Japanese context |

| |

To offer perspective to children that are under pressure of counselling systems I want to share experiences with Japan in this chapter. The concrete suggestion is not to take the school along in economic and political interests.

|

| |

| |

| If one single person is not happy, nobody is happy |

| Lessons for life as an answer to pressure, isolation and suicide |

| Last year the RVU broadcast the awarded documentary: “The Japanese lesson for life”, in the series Prospects (Vergezicht). There was a profound account in images of Mr Toshiro Kanamori, an inspiring, very authentic teacher who creates linkedness with and among his pupils against the conservative current. The film has been watched by many teachers and educational counsellors in the meantime. And the reactions are the same every time: people are deeply impressed. |

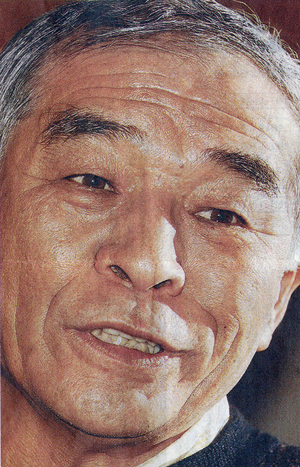

| Kanamori, philosopher and socio-historical free-thinker with a powerful human vision, has one wish: teaching children to become happy together. I had one wish: meeting this very special man! |

| |

| |

| Harmony and sense of community |

| In July 2006 I travelled to Japan for my search. In order to obtain insight in the Japanese educational system and historical influences I contacted Professor Dr Tsujii, educationalist and entrepreneur. It is not easy to describe the Japanese culture, of which education is a part, in a few sentences. Education itself is easier to describe: a strictly classical teaching with an unambiguous curriculum. In its appearance it is classical and traditional according to our standards; within the Japanese culture it is a self-evident form of education. The mentality of the Samurai (militaries) and the Shogun (one way, which you do not deviate from) can still be felt. Children enjoy a relatively high degree of freedom at an early age, which is restricted per year when they are going to school. The Japanese community is aimed at harmony. Expression is hardly visible. Emotions are shown as little as possible. Loyalty is common property. First there is loyalty to the company, next to your family. Employees work until late in the evening. An energy drink on your desk and going on until you collapse, is raising your status. You are showing at all times that you are available maximally for your firm, the place where your social life is set for the bigger part. The group has priority over the individual. In the small houses there is relatively little privacy. The Japanese person is there for Japan, an island of 120 million inhabitants, which has hardly looked across the water for years, but has now ‘the Western world’ as a big, modern example. |

| |

| |

| Much volume, little quality |

| Of course the national character and this education have brought the Japanese much prosperity in their economic flight after World War Two. But education only trains memorizing and makes ‘volume’. Containing a lot, having ready knowledge and being able to reproduce in detail. That makes the Japanese into perfect copiers. But it is ‘quality’ that is lacking. Innovation on one’s own initiative cannot or can hardly be found and is absolutely not stimulated. |

| |

| |

| Consequences |

| The children who have to study for hours, often attend two schools and sometimes even a summer school during the holidays, all of them are no longer able to resist this pressure. According to Professor Dr Tsujii there are at the moment some 1 million children at home, who are bending under the system and who do not dare to show themselves in public anymore for shame of their family. They are called ‘Ronin’ named after the Samurai who were violated in their honour and treated as outcasts. Also the number of suicides has increased frightfully. In trade and industry there is even a word for ‘death by overwork’ Karoshi. In 2006 147 people died because of working too hard and too long., 819 people became mentally ill and 176 people committed suicide or had a suicide attempt. |

| (source: ANP 17 May 2007) |

| |

| |

|

|

Documentary |

| The documentary is exceptional for Japanese notions, but also within our context it is highly exceptional. Mr Kanamori (he is 57 years old in the documentary) has been a teacher for more than 30 years. He worked at several primary schools. Teachers frequently attend his lessons due to his special vision and approach: he encourages children to enjoy themselves and tells that the children must confirm their own qualities as well as those of their friends and that they must have them confirmed. He wants a class in which children have a strong emotional bond and he passes ideas how this can be achieved in life. |

| |

| The film in group 6 starts with Myfoeyou, a girl whose father has died. She has so often told about him that she can do it with joy. During all kinds of activities the joy of the playing is visible. |

| Children are jumping into a river and into the pools on the muddy school yard. In June there arises a problem. Some children are bullied because of their report marks. Kanamori is concerned about the feelings of contempt that children have. He asks them ‘to look into their hearts’ and asks them to answer the question ”Why are you treating your friends with contempt?” Not a single pupil says about himself that he has been mean. Kanamori is angry when the children are blaming each other and want to keep out of harm’s way themselves. Everybody has to write a letter for the class diary. After reading the letters to each other and talking about them the children that were bullied and those who bullied, start to show their feelings. Yami stands up and she tells that she was bullied in the past (and starts crying). She knew how nasty it was, but when she remembered what it had been like to be bullied herself, she became afraid that it would happen again and said nothing. While she is telling this, she is passionately crying. Kanamori says he can understand this very well. He confirms the fear and the sadness. |

| |

| In October everybody is looking forward to the day that the self-made rafts will be sailing. The children have done everything themselves: from the design, the collecting of materials till the building. Now the moment is almost there; however, Kanamori is angry. Yuto has been chattering all morning and has not done what was required, despite several warnings. Kanamori is talking to him about it and asks the class why they did not talk to him about it. Kanamori says that Yuto may not join them on the raft-sailing. Yo and Omoto are in the same team and do not agree with his decision. They are revolting. They are delivering an emotional argument and say that his behaviour in class and building the rafts have nothing to do with each other. They want another chance for him. Mayuka is crying when she says that they really need Yuto. The class agrees that the punishment is not fair and that they will help Yuto to behave differently. Kanamori confirms the reasoning. The class starts to applaud. The orators are the heroes. Yuto can go along. The next day he writes in the class diary that he is sorry that he has caused misery and he thanks the children who stood up for him. He also thanks the children who cheered him up during to walk to the swimming pool where the rafts were launched. At the swimming pool Kanamori tells that he is impressed by the children’s ‘victory’. ”Being able to stand up for each other and to reason so purely is something even adults cannot do”. |

| |

| |

| If one single person is not happy, nobody is happy |

| On a small field behind the school a child tells what the lesson for life of Kanamori is: “We are going to school to be happy and to make each other happy. If one single person is not happy, nobody is happy.” |

| |

| In December Tsubasa’s father suddenly dies. The children would like to cheer him up, but realize that it is almost impossible. After school they take sweets to him ”He can eat a month on them.” All children write letters to cheer him up. Four days after his father’s death Tsubasa comes to school. He and his mother are impressed by the letters. One child is writing: “You have lost your father who used to call your name so cheerfully. I must cry when I think of it. We can do nothing about it. But if we can help you in another way, you must say so.” |

| |

| In Myfoeyoe’s letter who lost her father when she was 3 it said: ”Dear Tsubasa, I think you still grieve very much about your father’s death. But one day you will be able to tell about him. You must be strong now for your father. Do not brush this aside too quickly. Take care.” |

| |

| After group 6 they are going to different classes. They are talking about the farewell party. Yo and Kenta have an idea. During the class talk they tell that they have promised to take good care of Tsubasa after his father’s death. Now they want to let Tsubasa’s and Myfoeyoe’s fathers know they are cheerful and good friends. They are writing a huge letter on the sandy field outside with sticks and boards (each child a character) which can be read from heaven and they read them aloud together. They say goodbye and Kanamori writes on the blackboard: “forming a bond”. The children are in a circle holding hands and Kanamori tells that when it mattered his friends have always been there for each other and that they have understood the sense of life in that way. Laughing, crying, learning. The children now know how friendship bonds are made by respecting each other’s feelings. In that way they have learnt that having an eye for each other is the secret to become happy. |

| |

| Broadcast by “Vergezicht” (prospects) of RVU 2005 |

| Original title: “”Children Full of Life” Director: Noboru Kaetsu © NHK 2003 |

| |

| |

|

|

Meeting and talk |

| Kanamori studied pedagogic and philosophy at the faculty of Sport at the University of Kanazawa. In 1997 he was awarded an educational prize for his work and philosophy. His book ‘Full of hope in the classroom’ has been translated into Korean and has sold well. A talk with the 60-year-old Kanamori is a profound, emotional experience. He describes the substance of his acting and its justification. Kanamori is socio-historically well educated, knows the Japanese educational history, its consequences and he has based his vision on clear philosophies. |

| |

| After the First World War the authorities had one educational system. The same books, the same trainings. A will was imposed on people and the authorities determined everything. |

| Several ‘free teachers’ backed out of that system, but were all arrested during the Second World War. For Japan did not need any independent thinkers, it wanted a trained and obedient nation. |

| |

| Mr Kanamori is one of the few who have continued the line of the ‘free teachers’ after the Second World War. He noticed that relationships hardened and that the number of isolated persons (Ronin) and suicides increased frightfully. He was challenged as a philosopher to work with children and he was inspired by among others the Swiss-French philosopher, writer and composer Rousseau (1) and by the Swiss educator of the poor and educational renovator Pestalozzi (2). He shared their views and translated them into the Japanese context. Kanamori wanted children who were able to think themselves and who would be good for themselves and others. |

| |

| From a historical notion, the view on social tendencies and a study of the ‘free-thinkers’ he defined his own standards and truths. In a partition into five he gives the substances |

| 1. Children must be allowed to be children (they are not little adults): playing, having fun, feeling free, acquiring experiences with priority for their spontaneous vitality. Then he goes outside with the whole group and he plays together with them in the water, in the mud, in the snow. |

| 2. Children must eat well and must know the value of food. That is why the class eats together, talks about the food and grows their own rice and vegetables. |

| 3. Every human being is a unique being and he is all there. That is why Kanamori organizes many talks in which the children’s feelings emerge |

| 4. You may not put your own fate into the hands of others. It is also important to determine things yourself, to create and to take responsibility. That is why he has children organize things together without intervention of adults in order to reconstruct in case of conflicts from all perspectives. |

| 5. Children must be freed from the expectations of the parents. Children must learn to word their own needs, talk freely and take away the pressure that way. That is why he talks a lot with children about what occupies them and teaches them to argue. |

| |

| The Japanese culture is aimed at harmony and sense of community. “First the other person, then me.” The question if he thinks the relationship or autonomy is most important can hardly be answered. Of course autonomy is important within the context in which everything is directed at the relationship. And after thinking for a long time he says that people are all there as individuals to be able to mean something for others. He also thinks well-being and involvement are comparable entities and they are of evident significance. |

| |

| Two of Kanamori’s children died as infants. He knows as nobody else that circumstances are changing and can often not be determined. He did not become embittered, but he realized that life was full of dangers and mortal. That is why it is so valuable and why people make the effort to influence it as favourably as possible. Death gives life its value. Really enjoying things and being happy is the highest attainable. |

| |

| Because giving each other attention and imagining oneself in the other ‘are on the schedule’ Kanamori can express his lessons of life to his pupils in one sentence: “If one single person is not happy, nobody is happy.” And during those lessons Kanamori is not the only source of inspiration. |

| |

| |

|

|

A wheelchair rider, a pregnant woman and a terminal patient |

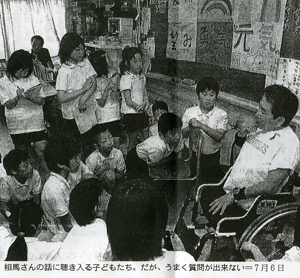

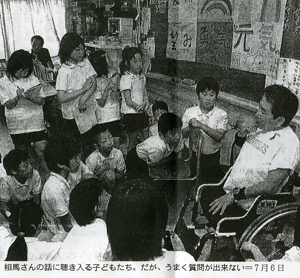

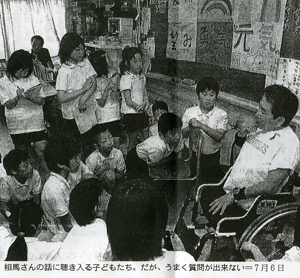

| One can read a few stories about his philosophies and guests in a Japanese newspaper. Yasuo Souma is an acquaintance of Kanamori’s and is in a wheelchair. When he was seven years old he broke his back and was paralysed in his legs. When he was 20 he had to have his legs amputated. He regularly visits Kanamori’s class. Then he shows the children a film about his life. He has “rolled” the marathon a few times. Kanomori has informed the children before and they have prepared questions, but when Souma enters the classroom, initially the children hardly dare to ask him any questions. But as soon as one child starts, more are to follow. They want to know if Souma has ever been bullied. Then Souma tells that he has not really been bullied, but that “he has seen the pain in other people’s eyes.” He tells how he considered suicide when a nurse put him in bath and confronted him with the body he could and should be happy with. She changed his attitude towards life. |

| |

| The children want to see his artificial legs and Souma moves from his wheelchair to the table onto a chair and back again. The children show admiration and do not think it is strange anymore. They believe Souma as he tells them that he is really satisfied and happy. |

| |

| Kanamori does not think that the children understand the impact, but that they can recall these images when they are confronted with them later. Then it will be easier for them to think from the other one’s perspective. “I have sown in their heads,” according to Kanamori, “now they may reap themselves.” |

| |

| One can read in the letters that the children write to Souma among others: “The nurse is a powerful woman.” “If you really want something, you can achieve much.” “I really am glad I got to know Souma.” |

| |

| Also highly pregnant women and terminal patients come and tell in Kanamori’s class about life and death. The women who are going to give birth to new life and the patients who consider their lives and everything worth while, tell what life is really about. Those are experiences which they share together and discuss in class. Another of Kanamori’s statements is: ”Being in the classroom is not the most important characteristic of education. Living is something you learn by playing in the world around you.” |

| |

| |

| Sport is not enough |

| During a hot summer it has rained heavily. The children have their swimming clothes with them (every school has its own swimming pool). The schedule says ‘language’ but that does not seem useful to Kanamori. He writes on the blackboard: “Listen carefully! Watch attentively! Love your entire body. You must receive the earth, the wind, the rain and the voice of your friends.” He tells they are going to play outside but that a “nice play” is not enough. Enjoying oneself is not enough. |

| |

| The children go outside barefooted and sit down on the ground. Kanamori asks if everyone will close his eyes. The children may pick mud and throw it, but they have to keep listening what is happening. When all the children are covered with mud they start gliding through the pools. Some children are hesitating and do not dare to do it. But when a number of children start everybody naturally joins them after some time. The fun can be seen and heard. Kanamori tells: “Children do not often play outside in Japan. Sport is important, but is often very competitive. Playing is different. It gives much wider experiences than competitive sports. Children must remain children to learn to play.” |

| |

| Kanamori talks a lot with children about their experiences. “The words of all children are important. Every day three children read aloud their written down experiences. They talk about these. If you talk together, children become familiar with each other. In the beginning they do not dare to express their opinions and to show their feelings. They start doing that as soon as they become familiar and if adults receive their words seriously.” |

| |

| I have become familiar and I have received Kanamori’s words seriously. Time to say goodbye. The headmaster walks me to the taxi and Kanamori… he is again teaching children how to be happy. |

| |

| |

|

|

Education and upbringing |

| Teachers as Kanamori do not distinguish between education and upbringing. They have an emancipated image of man; striving for equality, independence and honest, social relationships. That is why a beforehand determined programme is maximally partly possible. “Lessons of life” make you learn from the experiences that occur. That is why the combination of knowledge of education and the vision on upbringing is indispensable. So innovative, successful concepts are put into practice. Involvement becomes visible, well-being becomes perceptible. Empathic dialogues become ‘normal conversations’ in that way. |

| Linkedness is not a metaphor. And that is something we know for sure! Why? Because the children retell “the big story” in their own language. They are talking about their own happiness and that of others with lots of examples. And if children are able to share their positive, constructive experiences, the circle is completed. As round as the world in which Japan and the Netherlands can learn from each other. |

| |

| |

| |