4 |

As long as the conflict is cognitive |

| |

| |

| |

| Sticking and remaining |

|

|

| |

|

| “Marcel, come to me,” Rick calls. Rick is in group 3. He is sticking a piece of paper which he has folded himself on a large sheet of coloured paper. “It does not work. It does not stay in its place well.” I ask him where it does not stick. “Well, just not at all,” Rick says. “So you can simply take it of again.” Rick is smiling. “No, some parts stick a bit.” “Okay,” I react, “Just tell me where the figure does not stick.” |

|

| Cautiously Rick lifts the corners where the glue does not stick well. Without looking at me he puts glue on the ‘dry’ corners. He stands up and presses with his complete weight on the figure. “Yet, it is not good like this. It happened to me before. It will come loose in a minute.” I ask Rick if he knows other ways to press his sticking work. |

| |

| Rick is staring at his table for a short while. Then he looks at me smiling and cries: “The men in the corridor!” I immediately know what he means. There have been rebuilding activities for weeks in the school. Now workmen are laying a floor. They do so by pressing a pre-glued floor with a roll of eighty kilos. Rick and I are looking at each other beaming. Without exchanging a word we stand up at the same time and walk to the corridor. “Will you ask?” Rick says who is standing slanting behind me with his sticking work in his hands. “I will stay with you. You ask,” I answer him. Rick shuffles to the man who is laying the floor and who is handling the heavy roll. “Sir, my glue does not stick well. May I roll over it once?” Rick gets the apparatus in his hands. With the tongue out of his mouth and a tight face he pushes the roll across his sticking work. He pulls the roll back and pushes it forward again. He repeats this a few times with increasing pleasure. He thanks the man and proudly shows his strong piece of work to his classmates. |

| |

| I walk to the other side of the classroom where a group is working with bread dough. They make little pots. Mariska is making a lid. The form starts looking like it but she is not satisfied about the thickness. She calls to me: “How can I make it flatter?” Even before I can react Rick is showing his head above the cupboard. He calls smilingly: “I know.” He walks to Mariska, takes the lid that is on a piece of cardboard and says: “Take another piece of cardboard.” Rick is laughing so loudly that Mariska is following him nervously. When I am looking for them in the corridor, they ask for my watch. The floor layer has asked them to wait for another five minutes. Fife times sixty seconds they follow the thinnest hand on my watch. Rick has attracted some public with his gales of laughter full of expectations. Exactly after five minutes they get the roll. Rick puts the lid that is sandwiched between two pieces of cardboard on the floor. ”Help me push now,” is his instruction for Mariska. |

| |

| While laughing they are rolling three times up and down. The public has assembled around the roll. Under loud applause and yelling Mariska pulls apart the two pieces of cardboard. “It is flat enough like that!” Rick shouts. |

| |

| Within a short while the rebuilding will be finished. I am curious how the sticking and flattening will happen from that moment.

The reconstruction has yielded at least something. |

| |

If he does what he is good at

he does not do what I hate. |

| |

| |

| How do people develop? |

| |

| The constructivist way of thinking has become commonplace. Practically all modern methods and publications refer to constructivist predecessors and I also make use of them. In order to make choices it is important to create clearness in the first crucial question: “How do people develop?” |

| |

| |

| Constructivism in a nutshell |

| |

| In three clear steps the essence of constructivism can be explained. |

| |

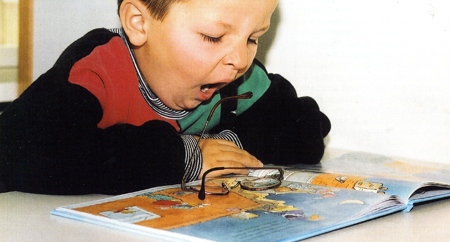

| 1) Reality is constructed at the mental level |

| Literally every human being had a different image of reality because reality is constructed from your own perception. And every person has a different perception. Sometimes that is clear: if somebody is (colour)blind or deaf but usually the differences are so shaded that a global observation shows little difference.

The difference in perception has big consequences for our interactions. If we say to people: “Look better,” “If you look well, you will see it,” “You can do it…” These remarks have a big impact on children’s self-esteem. They continually get arbitrary judgements on their actions. |

| |

| Ask yourself what you demand from children if you want them to ‘explain it to somebody else’. We know that children can sometimes do that better because they understand each other so well. The question is what they understand so well then. Perhaps it is true that they do not misunderstand anything in any case so that children do not have to guess what you mean. |

| |

| If handicaps or abnormities are clear we are not easily mistaken. We do not tell a deaf child to listen better. We do not tell a blind child to look better. But we do tell ‘normal’ children while everybody is deaf or blind in a way. It is often difficult to find out for what and to what extent.

An electrician can see the wiring through walls and the ceiling which are factually not visible. He ‘sees’ them because he knows where they are and what they look like. You do not see them (even if he asks you to have a closer look). |

| |

| A teacher can give the instruction: multiply supposing children have followed and understood him. He ‘sees’ the calculation, has references with regard to relevant structures and understands the context. Some children do not ’see’ that. The professional question is not: “How do you teach children to understand what you understand?” but “Are you capable of seeing through structures of the child in order to come to useful interventions from there.” |

| |

|

| |

| |

| From the developmental psychology a number of phases in learning can be distinguished. As long as the stages and the behaviour connected with them are recognizable and explicable for yourself, the guidance is usually based on acceptance. It becomes more difficult if you expect the other to be further in his development and more tuned to your patterns (“You may expect children of 11 years old to be able to …..”) |

| A well-known developmental psychological phenomenon with babies is object continuity. We see that babies are challenged by objects which are within their field of vision. If the objects are gone, they no longer exist. The baby does not ‘ask’ for the ball or the cuddly toy. That is self-evident for us. But if your colleague does not stand by his agreements (in the meeting we clearly agreed that everybody would hand it in this week) we can hardly imagine the regression. |

| |

| 2) Assimilation and accommodation |

| The orders with reference to ‘making’ reality from one’s own perceptions |

| The fact that every person builds his reality from his own perception cannot be misunderstood. We already learnt this from Piaget. That uniqueness has big consequences for the differentiated approach in an educational setting. It is important because of that complexity to view the systematic of ‘making reality.’ Developing and acquiring knowledge always happens through ‘Assimilation’ (being absorbed) and ‘Accommodation’ (tuning to). The organism absorbs something and tunes it. The absorption is determined by the environment and the possibilities of the individual’s absorption. The tuning is a deregulating process. |

| |

| 3) The dynamics of development |

Every person constructs his own reality. That happens through assimilation and accommodation. From science a phenomenon becomes visible which explains the dynamics of development.

The principle that every perceived difference between scheme (representation of reality) and reality is unacceptable for the mental system, starts a process of adaptation (adjustment, tuning). In other words: the environment presents itself differently from what you had in mind. That asks questions to your image of reality. And you want your image of reality to be square. So you have distilled a question from your environment which you want to be answered. In this way ‘intrinsic motivation’ and involvement present themselves.

You see kids being fascinated alternating interactions: kicking a ball, pushing a car, sticking paper, talking to a doll….

Also with adults ‘the process of adaptation’ is often clearly visible. Somebody is reading the paper and exclaims: “How is it possible that…” That is where it happens. The image of the reader’s reality is not in accordance with the reproduction in the paper. In the item the question presents itself.

We know how motivated we can get to solve our problems but we also know how unmotivated we can become because of dull, monotonous work. |

| |

|

| |

| |

| Cognitive conflict |

| |

If the environment presents itself differently form what you have got in mind, the environment asks you a question, you will get intrinsically motivated and there will be a ‘cognitive conflict’.

That conflict is the engine of developmental processes. Somebody who is challenged is enabled by a cognitive conflict to become involved so the schemes inside his head will change structurally and he will learn fundamentally. The new skills and knowledge do not stay behind in the book when the pupil leaves the classroom but they are stored in his system.

Within groups it can be easily discerned if children are involved or not. The difference is visible in the ‘conflicts’. In situations in which children cannot come to the real involvement there are often other conflicts. |

| |

Rather a cognitive conflict than another conflict. |

| |

| |

| Construction and re-construction |

| |

From the constructivist vision it is evident that development is an active process. We take into account the fact that it is cumulative, constructive, context bound, meaningful, self-regulating and purposeful. The ‘cognitive conflict’ is a self-evident stimulus to learn.

From the constructivist vision it also becomes visible what you can do if the development gets stuck. If the development has gone well the construction is visible. If developments get stuck there is a self-evident step: the re-construction. Reconstructing means rebuilding, re-composing. You try to imagine what happens inside the other person. You try to penetrate to the deeper meaning of behaviour. |

| |

| From there new possibilities can become visible.

An elaborate description can be found in the chapter about widening care. Below some examples will follow of small reconstructions which detect where children get stuck and indicate how they can get involved again. At reconstruction you must (sometimes intuitively) guess what children do already know and what they do not know (yet). But it is also important to ask yourself if children do not ask something different with their question. |

| |

| A language example |

Marlis (9 years old) comes to me with her text. One of the words she has written is: ‘stambeelt’ (statue). I tell her the word has not been written correctly and ask her if she wants to change it. I tell her that it is ‘stand’ and not ‘stam’. She did not know that so I do not let her guess. I do ask her if she has any idea why it is ‘stand-beeld’. She says: “Certainly because it is standing.” I wink at her.

Then I say that ‘beelt’ should also be different. She does not react. I ask her if she knows when you write a ‘d’ or a ‘t’ at the end. “Making it longer,” she says, “oh yes, a ‘d’ of ‘beelden’.” I ask her to write down five words with a ‘d’ and five words with a ‘t’ at the end as quickly as she can. She starts immediately. |

| |

| An arithmetic example |

| Stijn (10 years old) tells me he does not know the table of 7 very well. “I think it is difficult,” he says, “more difficult than the others.” “Which others?” I ask. “Well, I think those of 1, 2, 5, 6, 9 and 10 are easy.” “Why is that?” I want to know. “Well 1 time is 1 time, 10 is with a nought added, 2 times is 2 times, 5 times is half of ten, 6 times is one time more than 5 en 9 times is one time less than 10.” “That is a clever reasoning,” I say, “but if you know that you will only have to learn 3x7,4x7, 7x7 and 8x7.” Stijn walks away, writes them one under the other and he fills in what he already knows. Then he quickly calculates the four remaining sums and practises them. Then he comes to me with the information that he knows them. I ask them in order and mixed-up. He sometimes falters for a moment at the four new ones but ‘does know them’. In the afternoon I ask them again: during lunch, when playing outside, during project work. When I ask them again in the changing-room of the gym a few days later, he still knows them. “Easy as pie,” he calls. “And how you must learn a table is something you learnt form me,” he says proudly. He is right. |

| |

| A social-emotional example |

Rasa (8 years old) says she thinks arithmetic is difficult. “I do not understand it at all. I really do not know what I must do.” This morning she entered the classroom silently. I have not heard her all morning. She behaves differently from other times but I become aware of it that moment. She comes and sits besides me. “What did you do yesterday?” I ask. “Why?” she says. “Well, your sister came to fetch me and you had to leave quickly.” “Oh yes, we had to go to an aunt and there…”

And there the situation seemed different from usual. The family was concerned about an ill cousin. Her mother had cried and she did not exactly know what was the matter with her cousin. She tells me everything she knows and what she does not know. Then she is leaving again. She walks to her table and starts doing arithmetic. |

| |

| An example from the gym |

| Fenna (11 years old) is a shy and withdrawn girl. During tag she allows herself to be touched first as a frightened little bird. “Yes, it is no fun like that.” Cas shouts, “You must join the game!” But Fenna does not want to join the game as Cas wants her to. I see that Fenna huddles up when they walk into her direction and think there has to be a protecting space around her, before she can be touched. I have two trapezes put upside down in the gym. In each trapeze there may be one child. We play another game and when I call two names, they must touch the two children in the trapezes without getting into that space themselves. When I let Fenna sit down in one of the trapezes, initially she remains in a corner. Cas is interfering again. “No, you have to jump to the other side, so that they cannot touch you.” His instruction seems to work. The space is safe enough and every tagger she got freer. After some time she enjoys she cannot be touched. |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|